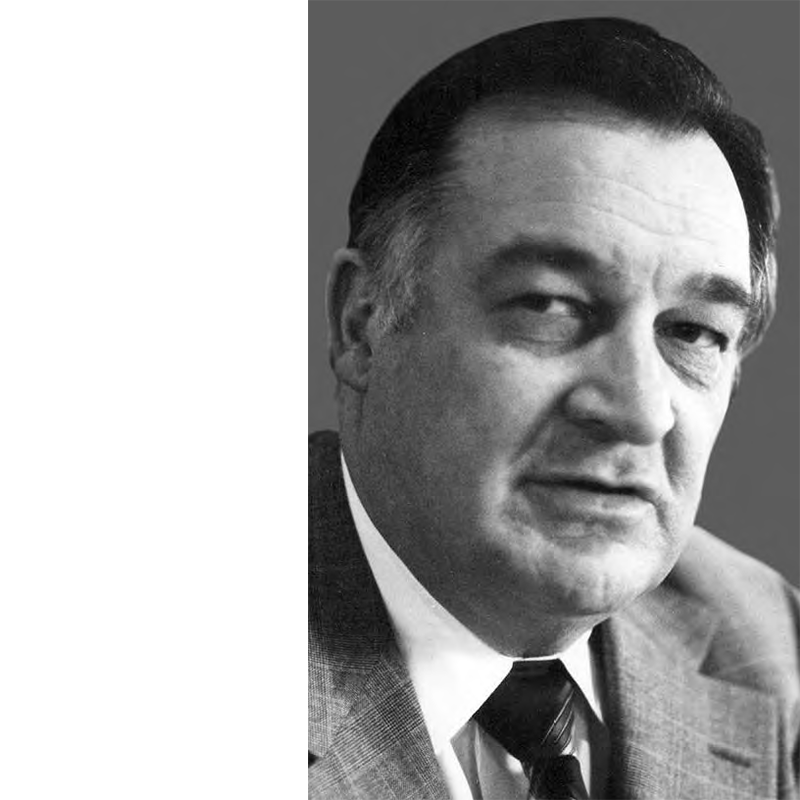

Stonie Barker, Jr.

Mining and Minerals Engineering

Class of 1951, BS

When Stonie Barker Jr., started his career, he never refused an assignment nor did he ever decline to go to an area he was needed, no matter how bad the conditions were. His philosophy paid off. He began his profession in mining as a deep-pit miner, and 19 years later he was the President of Island Creek Coal Company, the fourth largest producer of bituminous coal in the U.S. when he presided over the business.

For a man who would be described by Time magazine as a critical player in ending a three and a half month national coal strike in the winter of 1978, his adolescence, spent in a low-income area, never indicated he would become such a prominent leader in the energy arena. He was one of 29 students in his class at Chapman High School in West Virginia in the early 1940s. “You could stick under my thumbnail what I knew about math after graduating from high school,” the future engineering graduate recalls.

With World War II calling every able-bodied young American man, Mr. Barker enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1943, and he was sent to the South Pacific. He used the opportunity to enroll in math classes, but the courses still did not make up for his shortcomings. After the war ended, he worked as a common laborer, and questioned how he was going to make a living.

He enrolled at West Virginia Tech, and when he told his counselor he wanted to study engineering, “the man just shook his head,” Mr. Barker says. The counselor advised him to go back to high school math classes, which he did during the summer of 1947. Later that summer, he accompanied a friend to Virginia Tech, and while he was on campus, he visited the Admissions Office. He summoned up his courage and asked if he could enroll. The immediate response was, “Do you think you can just walk in here like it is a restaurant and order a sandwich?” Barker remembers vividly. Undaunted, he told the gatekeeper that he had been overseas in the military, and the atmosphere in the room changed immediately. He was on Virginia Tech’s roster that fall, using the GI Bill to pay for most of his expenses, leaving him with the sum of $132 a quarter, or $44 a month, to pay for his room, board, and tuition.

Steadfast in his intentions, the young man graduated in 1951 with a degree in mining engineering. His West Virginia roots led him to the only industry he knew might have opportunities for him. “Coal mining is a tough industry physically, but it had opportunities for educated people,” Mr. Barker, the former president of the student chapter of the Burkhart Mining Society at Virginia Tech, says. He immediately joined Island Creek, which began its operations on 30,000 acres of land in Logan and Mingo Counties in West Virginia in 1902.

Mr. Barker started with the company’s training program, learning all the phases from safety to productivity. After six months with the industrial engineering department, he moved to operating management. During this time, he spent about six years underground. He recalls one of his most difficult assignments was when he accepted the supervisory role of a Breathitt County, Kentucky, coal mine that was about 30 inches high. Mr. Barker, a large man, had to crawl with his employees on his hands and knees through the mine. “No one wanted this job, but the company told me if I could make it profitable, I could write my own ticket,” he says. Within six months, the mine became profitable and Mr. Barker was named a superintendent.

Within 12 years of his graduation as a Hokie, Island Creek named Mr. Barker its vice president of operations. Seven years later he was president, and by 1972, the chief executive officer. In 1983, he was named chairman of the board. During his career with Island Creek, its coal production rate doubled, growing from 16 to 32 million tons annually. “I had good tutors,” he says, specifically citing the late Nick Camicia, a 1938 MinE graduate of Virginia Tech, as a person he relied on as a mentor.

Mr. Camicia, also a member of Virginia Tech’s Academy of Engineering Excellence, and Mr. Barker remained friends throughout their careers, even after Mr. Camicia left to preside over a competitor, Pittston Coal Company. The camaraderie between them was a key factor in dealing with the strikes by the United Mine Workers (UMW) union in the 1970s. A particularly onerous one that lasted through the winter of 1978 had the Bituminous Coal Operators’ Association (BCOA) at odds with the UMW led by the reformist Arnold Miller. When the BCOA, of which Mr. Barker was chair at the time, and the UMW could not reach a settlement, Mr. Barker suggested to Mr. Camicia that they speak directly to the UMW representatives, and not use the mediators. As both had spent many years in deep pit mines, they were able to remove the logjam between the groups, and had a deal within 24 hours.

“The UMW saw we did not have horns. They knew who we were. They spent a lot of time talking about the hard line approach the previous negotiators, the lawyers, had taken. They were glad that somebody was working with them who understood what mining was all about,” Mr. Barker said in an interview with his alma mater after the negotiations in 1978. And today, he still feels good about that satisfying time in his career. “Labor was tough, and they would strike at the drop of a hat. It was most rewarding to turn that around.” He was named chair of the BCOA following the settlement in 1978.

Today, Mr. Barker, named the Coal Man of the Year in 1985, predicts the coal industry still has a good future, but it must learn how to burn it cleanly and not pollute the atmosphere. “This country can’t do without coal ... The country will demand it, use it, and do it cleanly. We are making headway,” the chair of the National Coal Association from 1982-84, says.

Retired in 1984 from Island Creek, Mr. Barker now divides his time between his homes in Hendersonville, North Carolina, 22 miles south of Asheville near the Blue Ridge Mountains, and Naples, Florida, along the state’s Paradise Coastline. After his first wife died in 1998 after 47 years of marriage, he wed for a second time in 2003. He and his wife, Dorothy, enjoy playing golf together, and spending time with their children and grandchildren.

As a parent, Mr. Barker spent hundreds of volunteer hours with the Boy and Girl Scouts of America, and continued supporting them after he retired. In his own youth, he never had the luxury to become a scout as he spent his spare time earning extra money. But he made sure his son, Douglas, and daughter, Beverly, had the opportunity. Mr. Barker helped raise enough money for the local troops in Logan County that they were able to erect a winterized troop house that he predicts will be there “for 100 years.”

Mr. Barker is a member of the Virginia Tech College of Engineering Committee of 100 and he funded the Stonie Barker Professorship of Mining and Minerals Engineering, held by Michael Karmis, mining and minerals engineering professor and director of the Virginia Center for Coal and Energy research, an interdisciplinary facility for the state. Two of VCCER’s focuses are clean coal technology and carbon sequestration research.

Class of: 1951

Year Inducted into Academy: 2009