The Joseph F. Ware Jr. Advanced Engineering Laboratory was a product of the right time, the right place, and the right people.

Ask any Virginia Tech engineering student about the Joseph F. Ware Jr. Advanced Engineering Laboratory, and odds are they’ve stepped foot in it.

Arguably the most popular lab on campus and hallmark of the Virginia Tech undergraduate engineering experience, the Ware Lab is a 10,000-square-foot facility, split into nearly a dozen bays full of tools, materials, and student design projects. It’s home to award-winning teams like Hyperloop at Virginia Tech, Human Powered Submarine, ASCE Concrete Canoe, and more.

But before there could ever be a Ware Lab, Joe Ware had to meet his future wife, Jenna.

Without Jenna, the plans for the lab might never have been drawn, the old Military Building might never have been converted, and thousands of students may not have experienced the unique hands-on experience that comes from working on a project in the Ware Lab.

To the boon of generations of engineering undergraduates at Virginia Tech, Joe did meet Jenna, in 1989 at Camarillo Airport, about an hour northwest of Los Angeles. The two initially bonded over their mutual love of flying and before long were inseparable.

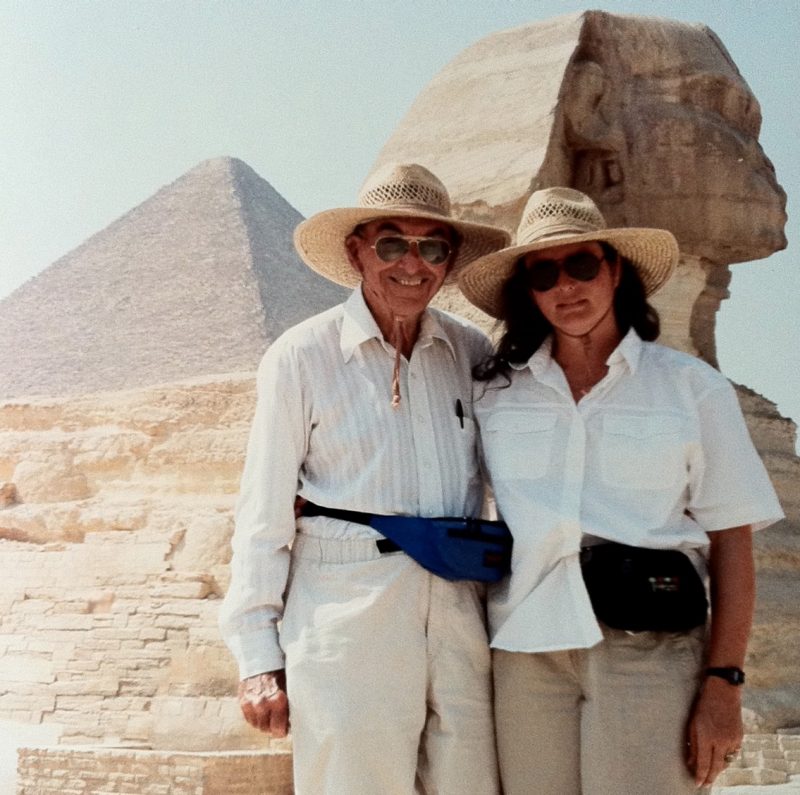

In the years that followed, the pair got married and traveled the world, flying their personal planes all over the continental U.S. and taking commercial flights to Israel, Egypt, England, and France.

Occasionally, they’d stop in Blacksburg, Virginia, to visit Joe’s old stomping grounds. The son of a Virginia Tech professor, Joe grew up in Blacksburg at 404 Clay St., and, at the age of 15, enrolled at Virginia Tech.

He graduated in 1937 with a degree in mechanical and aeronautical engineering, then went to Caltech for a master’s degree in the same area, graduating in 1938.

Joe returned to Virginia Tech to teach mathematics and was hired in 1941 as a flight test engineer at Lockheed under Clarence “Kelly” Johnson at the Skunk Works, Lockheed’s premiere project development division that designed the world’s fastest and highest flying airplanes, including the F-104 Starfighter, U-2, and SR-71 Blackbird. Joe also helped with the first two Air Force One planes during President Dwight Eisenhower’s administration.

It was after one of Joe and Jenna’s trips to Blacksburg, during which the pair had visited with students who were building an autonomous vehicle, when Jenna came to Joe with an idea.

“We’re at the house — and Joe had talked about the Skunk Works for a few years — and I just sat around and I said, ‘Joe, the students need a Skunk Works up there,’” Jenna said. “He agreed.”

So she began to brainstorm. Jenna envisioned a wide open, one-room space stocked with tools and complete with a bay door for moving bigger projects in and out.

“This kind of a working lab was what I envisioned as a Skunk Works,” Jenna said.

The couple shared the plans with Virginia Tech. It turned out Hayden Griffin, professor and head of the Department of Engineering Education at the time, had already been leading a similar idea with a few other faculty and some funding from the university, thanks in large part to the late former university provost Peggy Meszaros and Susan Sink, the former director of development of the College of Engineering.

Griffin was building on an idea championed previously by Robert Comparin, professor emeritus and former mechanical engineering department head, who started the original “Car Factory” at Virginia Tech.

When Griffin and the Wares joined forces, “it was a marriage of ideas,” Jenna said.

Because of a generous monetary donation from the Wares — and the full and unyielding support of Dean Emeritus Bill Stephenson — the Ware Lab opened on Sept. 4, 1998.

Other donations followed, including sponsorships from industry and a gift from Arthur Klages, a 1942 industrial engineering graduate who founded the Burlington Handbag Company and invented of a number of mechanical devices used in the garment industry.

His donation of machine shop equipment — including a lathe, mill, drill press, and bins full of bits and tooling — led to the creation of the Klages Machine Shop, where students can access various advanced machine tools used for project manufacturing, including two computer numerical control machines.

Almost 20 years later, more than 400 students a year collaborate on research and design projects in the Ware Lab. From redesigning a Chevrolet Camaro to be more fuel efficient in the Hybrid Electric Vehicle Team bay, to building a small formula-style racecar in the Formula SAE bay, the Ware Lab is where undergraduate engineering majors go to gain real-world, hands-on experience as early as freshman year.

“The Ware Lab provides students with an opportunity to apply engineering concepts in controls, structures, mechanical design, and electrical theory in real time,” said Dewey Spangler, manager of the Ware Lab. “Students take classes in these and other subjects and then utilize knowledge gained in a controlled, immersive atmosphere. They also have the opportunity to sharpen public speaking skills by meeting with visitors who tour the facility each year.”

Working on a project in the Ware Lab provides students important experience — over 90 percent of the students on the Hybrid Electric Vehicle Team’s EcoCar3 project found jobs right out of college or were accepted into graduate school.

Genevieve Gural, a fifth-year senior studying mechanical engineering from Clifton, Virginia, has worked since the second week of her time at Virginia Tech with the lab’s Baja team, which participates in a national competition to design, build, and test a single-seat off-road vehicle.

She’s currently team lead. Once she graduates in May, she’ll start an internship at Tesla, an innovative and world-renowned automotive company founded by Elon Musk.

“The Ware Lab is the main reason I was offered this internship. Tesla came to campus, reached out to Ware Lab teams specifically and said, ‘we want to meet you,’” Gural said. “They came directly to students working on projects like Baja, Formula, the Hybrid Electric Vehicle Team, and BOLT.”

Gural attributes her hiring at Tesla — and at SpaceX for co-ops and internships previously — to the skills she’s developed working in the Ware Lab.

“The reason that they recruit so heavily from us is because they know that our project teams are very analogous to industry. The skillsets you learn here are highly transferable to what you’re going to do over there,” Gural said.

Following a prolonged illness, Joe died in 2012 at the age of 95, but his legacy lives on in profound ways.

As Joe became sick and developed Parkinson’s toward the end of his life, he still wanted to fly. Jenna would take him out to the airport where they met, strap him into their Cessna Cardinal, and head for the sky.

Before he died, Joe and Jenna had been together 22 years, married 17 — but it wasn’t always easy.

Jenna was in the U.S. Navy in the 1970s, in the National Security Agency’s National Security Operations Center in Ft. Meade, Maryland. As of 1981, she is transsexual, and has dealt with related discrimination all of her life, including from colleagues and her own family. Because she had been hurt by people who had known, she entered “stealth mode living” in general and in her profession as a clinical social worker. Through most of life, she felt she could not own who she was.

But she found refuge in Joe, despite an age gap and their complete political and religious differences.

“Joe was a conservative Christian Republican 40 years older, and I am a liberal Democrat Jewish transsexual — and I call that a mixed marriage,” Jenna said.

The only reason this marriage of opposites could be was because, according to Jenna, Joe “had no concept of prejudice” in his heart. In fact, Jenna was the one who took longer to warm to the idea of loving Joe, but she learned from Joe’s open-minded example, and the two wed in 1995.

She wasn’t the only one who benefited from Joe’s teaching. Jenna remembers the way Joe interacted with students. Though he was soft spoken, he asked sharp, insightful questions until the concept was fully understood.

“Joe always knew how to find the answer,” she said.

So do the students in the lab with his namesake. Like Joe and Jenna, students in the Ware Lab come together from different backgrounds to create something new and don’t shy away from tackling difficult questions.

Even though Joe is no longer here to see it, his brand of ingenuity and curiosity lives on in the lab through the students and their collective vision of engineering the future, and his spirit lives on in Jenna.

She keeps two of Joe’s old baseball caps on a shelf in the back of her cockpit — one from Caltech and the other from Virginia Tech. When she’s in the sky, she feels closest to Joe, like he’s right there flying with her.

“When he’s part of your neural pattern, and then he’s gone, the neural pattern remains,” Jenna said. “He’s in my heart, and I don’t want him to leave. I like him there.”

If you want to have an impact on our students and faculty like those featured in this magazine, go here to support the College of Engineering. For more information, call Lindsay Arthur, advancement associate in the College of Engineering, at (540) 231-3628.

-

Article Item