The Hyperloop at Virginia Tech team may have started with a simple Reddit post, but their race to invent the next major form of transportation has the undergraduate team tackling a complex engineering question.

On a Sunday night 15 minutes before midnight in early November, a group of undergraduate engineers is still wide awake. They’re stationed at TechPad, a local coworking space, trying to figure out how to not catch their Hyperloop pod on fire.

“So, could we find a more efficient way in a triangle configuration?” asks Bobby Smyth, a senior from Yorktown, Virginia, studying mechanical engineering, who’s trying to figure out the best way to arrange an array of batteries inside a pressure vessel.

“Oh, you’re saying if we did a cylindrical pressure vessel?” asks Eric Plevy, a senior from Durham, North Carolina, studying aerospace engineering and aerospace and propulsion lead for the Hyperloop at Virginia Tech team.

“Yeah,” says Smyth, the chief engineer. “This is really driven by fitting inside the skin.”

They go back and forth, trying to create a pressure vessel that not only works, but can be contained in the carbon fiber shell housing the complex systems inside the Hyperloop pod they’re building from scratch.

This is but one in a series of problems they have to solve — problems that have no definite answer in a textbook — in their quest to create a pod that can race through a vacuum chamber at speeds upward of 200 miles per hour.

Hyperloop is a concept, pioneered by Tesla and SpaceX founder Elon Musk, for a high-speed transportation system that uses a near-vacuum tube to propel a passenger-carrying pod at speeds eventually in excess of 750 miles per hour. The idea, if realized, could turn a 3-hour commute from Washington, D.C., to New York City into a 30-minute trip.

The Hyperloop at Virginia Tech team is currently designing their third pod iteration for the upcoming Hyperloop Pod Competition III, to be held on SpaceX’s Hawthorne, California, campus in summer 2018.

The team has been involved with the competition since Musk’s announcement of it in June 2015 — and it all started with a Reddit post in that summer by mechanical engineering student Adi Maini, who graduated in spring 2017.

“Is anyone making a hyperloop team at Tech?” he wrote on the social platform known for discussion threads and news aggregation.

A reply to the thread connected Maini with another mechanical engineering student named Christian Olivo, who was also looking to start up a team.

“We chatted and then called each other to discuss what our next steps should be,” Maini said in an email. “We decided to post on social media groups to get more interested students together.”

The momentum built and other students joined, namely Alex LePelch, Daniel Kimminau, Nathan Roberson, Matt Barnes, Keith Baum, and Allison Quinn, who formed the basis of the founding group (Kimminau, LePelch, and Roberson all currently work for SpaceX). By the group’s second meeting, Plevy also joined.

Plevy remembers hearing about the formation of a Hyperloop team at Virginia Tech from the Reddit post. Just before that, during his sophomore year, he had read the white paper Musk released and found the futuristic concept of a Hyperloop fascinating.

So when a friend from another design team Plevy was on told him he was going to a Hyperloop meeting, Plevy tagged along. He’s been with the team ever since.

“It really was very motivating to be on such a cool team of about five or six people just to start with,” Plevy said. “And that kind of added to the fact that, ‘Hey, I'm kind of inventing a fifth mode of transportation right now,’ so it's just — it was an incredibly cool concept combined with just brilliant people that I got to work with.”

Plevy said the group met in the library at first, trying to sort out their organization.

“We didn't have any solid design ideas, no foundation for technical information; we just kind of were talking about how we're going to structure the team at that point,” Plevy said.

They began working out of the Computer Aided Design Lab in Randolph Hall as they continued growing the team.

Even with a lack of funding while they were getting on their feet, the team began designing a pod for the first portion of the competition, the Hyperloop Pod Competition Design Weekend in January 2016 at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas.

“There were many nights where we didn't sleep,” Plevy said. “I mean, this is kind of a common theme between every team that we've had thus far and every competition, but especially at the beginning, in order to get notoriety and basically become recognized as a team, we had to prove to them that we were capable of it.”

When they showed up to the design competition, they were prepared to do well, but even Plevy said they didn’t know they would end up placing top five. They took home fourth place and a Technical Excellence Award against more than 120 teams representing many of the top universities in the world.

Then came the funding opportunities. The team was approached by big name startups and well-established companies alike looking to fund them, including Hyperloop One, Cooley, ANSYS, and Performance Associates.

“It was all overnight,” Plevy said.

They came back to Virginia Tech, where they would soon begin working out of a lab space on Inventive Lane, and began to get ready for the next competition where they would actually debut a built sub-scale Hyperloop pod and race it in a mile-long vacuum tube test track near the the SpaceX campus in Hawthorne.

For the January 2017 competition, the team debuted their first pod, the Vhyper. The first competition prioritized both excellence in design and speed, but the team decided to strategically use the first competition to test their passive magnetic levitation, opting to not use a cold gas thruster propulsion system.

They placed fourth out of 27 entries, then the cycle of preparing for the next competition began again. The Hyperloop Pod Competition II, held in August 2017, was focused purely on speed, so with their new knowledge from the first competition, they made slight adjustments to their original pod.

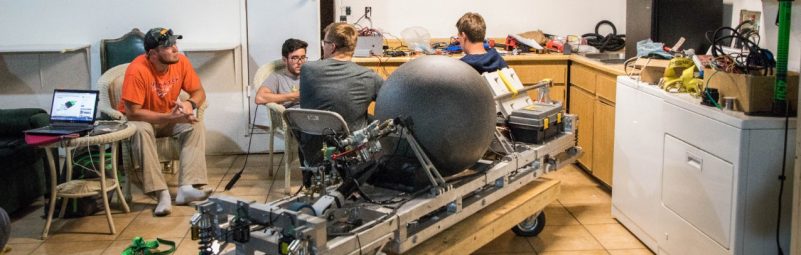

At Pod Competition II, the team debuted V17, a 600-pound pod with a carbon fiber shell. They implemented the cold-gas thruster, consisting of a large spherical tank. The team estimated that the pod could run upward of 50 mph, fueled by compressed high-pressure nitrogen and aided by an additional 90-120 miles per hour from the SpaceX-designed pusher on the test track.

During the week leading up to the final competition, the 11 students in attendance worked to certify their pod through rounds of preliminary checks, including a structural test, a navigation test, a functional test, propulsion approval, and a vacuum chamber test. The team was able to defend the design of their pod to SpaceX representatives — one of the requirements of being able to race due to the potential safety hazards associated with sending a pod through a near-vacuum chamber at high speeds.

The team was not selected by SpaceX to be one of the three teams to compete in the external Hyperloop test track on competition day, but it did complete many of the prerequisite tests with their pod.

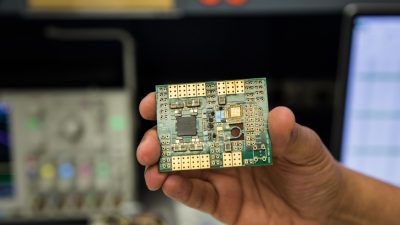

While theoretically the pod would have been ready to run on the track, the team ran into complications with the electronics as they integrated the system. The team used quick thinking and multiple trips to home improvement and electrical stores to address issues as they found them.

Smyth, who joined in summer of 2016 and has interned at SpaceX, says the most recent round was a learning experience that emphasized the value in completing tests on their systems earlier, while in Blacksburg.

“Your success in the competition is a function of how well your system is tested,” Smyth said. “When you go out there, the SpaceX engineers want to be able to see that you understand your system, you understand what the failure modes are, and you perform the correct tests to alleviate those failure modes.”

Those imperatives have shaped the philosophy of the team as they prepare for the third competition next summer. So far, team members have worked long hours at TechPad on their pod redesign. They plan to strip out the propulsion system and add on an electric motor.

Since the third round of competition focuses on speed, they’re also optimizing the shell of the pod itself. They’re using a carbon fiber monocoque design, which will cut down on the mass of their system, thereby allowing the pod to go faster.

“There's a bunch of complexities that go into that,” Smyth said. “The way you do your analysis for a composite material is very, very different from the way you do it for metallics. So we have to learn a lot of new techniques and softwares and skills in order to be able to adequately analyze our system.”

And that’s just what they plan to do, despite the workload it requires. For the members of Hyperloop at Virginia Tech, participating in Hyperloop is, according to Smyth, “an outlet for creativity in designs,” a welcome addition to learning more theoretical concepts in class.

“In a competition like this and a lot of other design teams, it’s really up to you, the student, to find those solutions and find that path,” he said.

Should they be able to do it, this Virginia Tech student team will contribute to some of the most compelling technology of our time.

If you want to have an impact on our students and faculty like those featured in this magazine, go here to support the College of Engineering. For more information, call Lindsay Arthur, advancement associate in the College of Engineering, at (540) 231-3628.

-

Article Item