Virginia Tech's Center for Power Electronics Systems had humble beginnings, but the growing importance of the power electronics field — and founder Fred Lee's tenacity — ensured that didn't last long.

The story of the Center for Power Electronics Systems begins in a single room in Patton Hall.

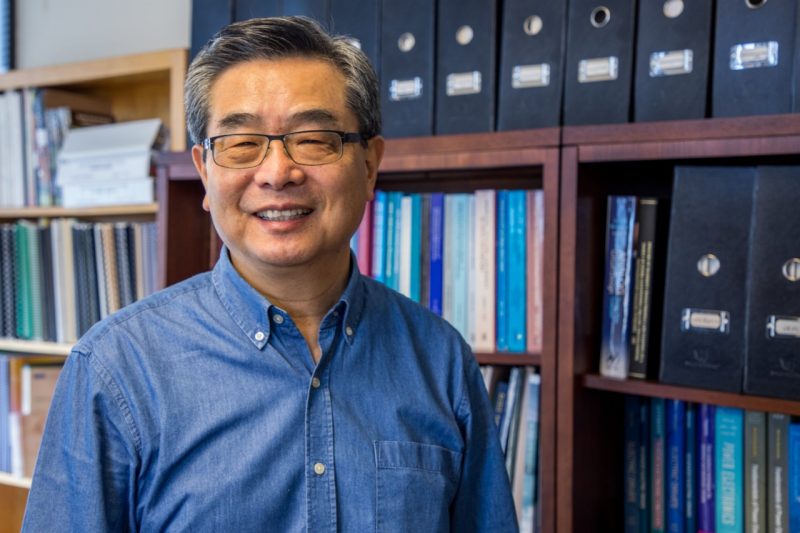

Fred Lee, at the time a new addition to the Virginia Tech faculty, decided to establish a lab that focused on the small but growing field of power electronics. It was 1983.

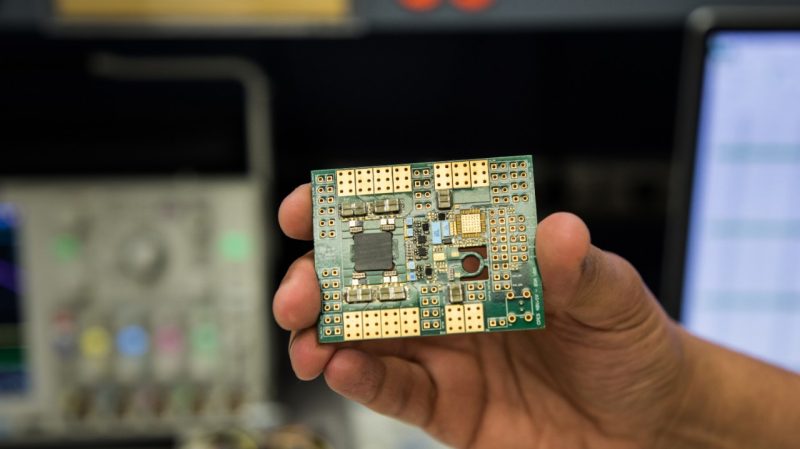

Today, power electronics touches nearly every aspect of modern life: cell phones, laptops, and electric vehicles, for instance, all make use of the technology. Correspondingly, CPES ballooned into the lab it is at present, spanning the entire first floor of Whittemore Hall and expanding its presence into the National Capital Region, with more than 50 graduate students working on projects for company partners.

Lee, now a University Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Bradley Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, retired from Virginia Tech in September 2017, leaving the lab to its newest director, Dushan Boroyevich, University Distinguished Professor and American Electric Power Professor in the same department.

After 40 years at the university and in the College of Engineering, Lee, who is also a member of the U.S. National Academy of Engineering, has made immeasurable contributions to the field of power electronics including: earning more than $100 million in research funding; supervising 84 Ph.D. students and 93 master’s students to completion; filing 104 patents (82 of which so far have been awarded, with the rest pending); becoming one of the top three most-cited engineering authors out of over 1 million, according to the Microsoft H index; and publishing more than 290 journal papers and 710 refereed conference papers.

Yet, from the beginning, Lee’s immense career in power electronics was serendipitous.

After completing a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from the National Cheng Kung University in Taiwan, Lee came to the United States in 1969 and enrolled in a master’s program at the University of Missouri. His fiancee, Leei Wong, was studying at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — 918 miles away. Lee closed the distance by transferring to Duke University, where he suddenly needed to find funding.

That’s when Lee met Tom Wilson, a professor in Duke’s Department of Electrical Engineering, who would change the trajectory of Lee’s career.

“This professor ... has money. And he is also the most well-known in the department,” Lee said of his thoughts at the time. “So I got the money, and I got the famous professor. Why not? Whatever he does, I am willing to learn.

“That's how I got into power electronics," Lee said, laughing. "In my generation, almost everyone got into power electronics by surprise, by accident.”

Lee explained that, at the time, no one could have predicted the importance of power electronics. But the rise of the aerospace industry — coupled with the rebuilding of Japan following World War II and the adoption of electrified mass transportation in Europe — thrust the field into the international spotlight.

Lee witnessed this evolution — and the most recent boom — and was actively part of it.

“I lived through it,” he said. “When I teach a class, I am basically teaching my life.”

Long before he would set foot in the classroom, Lee worked in industry. After earning his master’s degree in 1972 and his Ph.D. in 1974 from Duke, he ventured out west to California to work at aerospace- and automotive-focused corporation TRW Inc. After three years, Lee was tired of a two-hour commute to and from Los Angeles, where “there is no winter.”

“I really missed the four seasons,” Lee said. "After three years, I decided I had to move somewhere on the East Coast, to a small town, not a big city. Since I knew what industry life was like, I said, 'Maybe I should try academia. I don't know what it is. Let's give it a try.’"

Much to the confusion of interviewers at several universities, Lee took a significant salary cut and went into academia — once telling an interviewer that they could pay him ‘whatever.’

In 1977, Lee was hired as an assistant professor of electrical engineering at Virginia Tech. Three years later, he became an associate professor, then a professor three years after that.

In 1983, he founded and became the director of the Virginia Power Electronics Center, a precursor to the 1998 founding of CPES. Lee was also honored in 1998 by Virginia Tech with the University Distinguished Professor distinction.

Lee established Virginia Tech as the destination for leading researchers and educators in power electronic systems worldwide. His successful industry affiliates program has been replicated by many other groups across the university.

please span across the page

Lee’s work with CPES was one of the defining elements of his career. The industry consortium became a model Engineering Research Center (ERC), as designated by the National Science Foundation.

“Fred delivered on his bold and ambitious vision to create a center where researchers from Virginia Tech and partner institutions could collaborate hand-in-hand with industry affiliates to radically transform electronic systems-level technologies that are used to power everything from microprocessors to electric vehicles to cities,” said Theresa Mayer, vice president for research and innovation at Virginia Tech.

During the 10-year NSF ERC program, CPES teamed up with 96 industry partners and five universities, with Virginia Tech as the lead institution.

“His inspirational leadership of CPES for over 30 years has made Virginia Tech the global destination for top researchers and educators in power electronic systems and their applications,” Mayer said.

In this 10-year period, the center has received $30.4 million in funding from the NSF and $57 million in funding from industry, government, and institutional support; graduated 153 Ph.D. and 176 master’s students; published more than 3,100 technical papers, theses, and dissertations; filed 286 invention disclosures; and was awarded 103 patents.

Yet, it’s not the center’s accomplishments that inspires Lee the most; it’s the growth he sees in his students.

He beams when he tells the stories of his students’ successes, both in industry and academia. Former students regularly visit or write to Lee, telling him anecdotes of his influence that even Lee doesn’t remember. Often, students will come back to form partnerships between their companies and CPES.

“They listened to me before, now I listen to them,” Lee said.

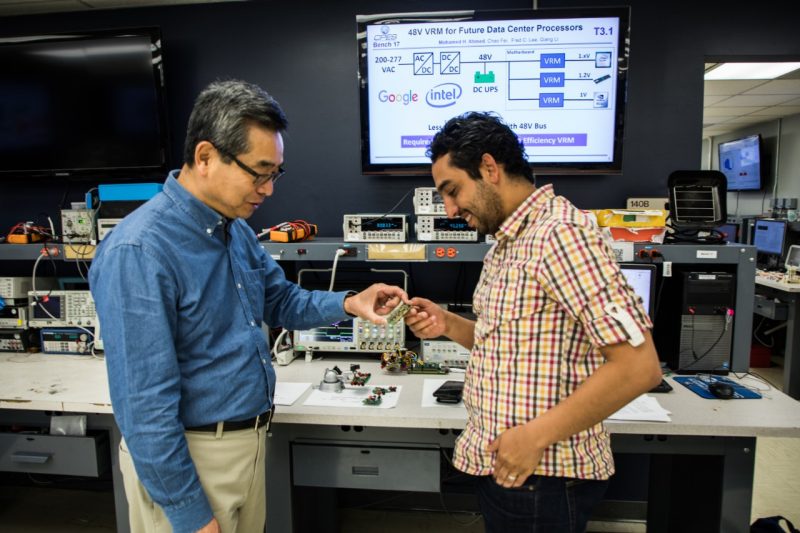

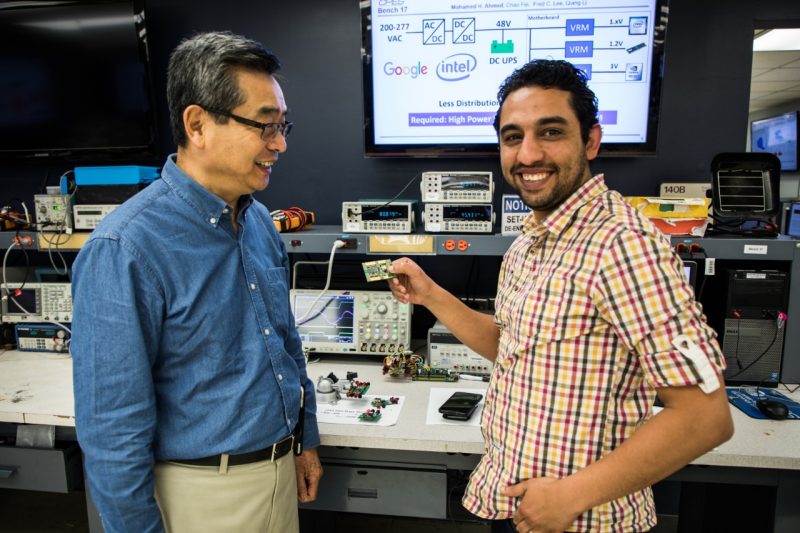

Perhaps the closest of such relationships is that with Dushan Boroyevich, University Distinguished Professor and American Electric Power Professor in the Bradley Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. After graduating with a doctorate earned under Lee's guidance in 1985, Boroyevich returned to University Novi Sad in Yugoslavia to become a professor and later the department head.

Lee personally recruited Boroyevich — as he does with most of his students — by traveling to Yugoslavia in 1990 to convince him to return to Virginia Tech.

For more than three decades since, the pair have been “side-by-side,” Lee said.

“Fred is forever challenging us to understand. All of his students and coworkers recall months of trying to explain to Dr. Lee their new ideas and constantly being challenged, even about basic assumptions and concepts,” Boroyevich said. “Finally, in frustration, you are not sure if you are completely incapable of understanding anything … until you accidentally overhear Fred telling someone else, ‘This is the best idea I’ve seen in a long time. You should use it!’”

Lee hopes he made one thing clear to all of his students over the years: “I'm trying to drive hard to their mind that you have to discover your limit,” Lee said. “And my message basically to them is: There is no limit. You have to push yourself, then you begin to realize what you consider impossible is actually possible.”

Lee credits Wilson, his professor at Duke, with teaching him this attitude, which Lee said was the single most important lesson of his career. In his retirement, he hopes to continue passing this mentality down to students through his mentorship of junior faculty members in his department.

Rather than have his own students or take on the role of principal investigator for grants, Lee, as a part-time professor, “will give every opportunity to junior faculty members,” he said.

Meanwhile, Boroyevich will carry on the torch of CPES as the center’s new director.

“While keeping our program strong, we will work with Virginia Tech administration to develop physical and organizational infrastructure for the growth of CPES, increasing to 10 professors, 10 staff, over 100 graduate students, and over 100 companies in our consortium,” said Boroyevich.

“The goal is to increase total external funding to $10 million annually in the next five years, expand in two new cross-disciplinary areas and in two locations: Blacksburg and Washington, D.C., area.”

Boroyevich, who is also a U.S. National Academy member and University Distinguished Professor, plans to explore cross-cutting research and education at the intersection of engineering, architecture, business, and other disciplines.

“This exploration will enable pervasive changes in the way electricity is used,” Boroyevich explained.

By doing so, Boroyevich is confident the center will build upon previous work in order to transform living and working spaces into enjoyable, healthy, efficient, and attractive environments – without the clutter of electrical cables, air ducts, electromechanical switches, and power outlets.

Similarly, low-cost versions of these new technologies could revolutionize rural electrification in the developing world by using local renewable and distributed generation without connection to the national grids.

This is what Boroyevich calls a “bottom-up-grid” approach to solving some of the greatest challenges facing modern society.

As for Lee, it’s his turn to enjoy some downtime in retirement. He plans to do more fishing and golfing and wants to travel and visit some of the dozen universities across the globe where he has served as an honorary professor.

As for where he plans to retire, Lee won’t be giving up his four seasons anytime soon.

“I've been looking for a place to retire for the last 10 years,” he said. “I gave up. Blacksburg is the best.”

Lindsey Haugh contributed to this story.

-

Article Item