Since its onset, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented student design teams — groups used to troubleshooting small snags and big setbacks — with a wave of new challenges for their design cycles.

Virginia Tech’s Design, Build, Fly team was on its fifth plane when the nosedives stopped. At 20 feet long, the remote-controlled, banner-towing bush plane the team had designed for the 2020 competition season was the longest they had ever built.

Its wing was long, too, at five feet, and that had caused the nosedives: the boom, a rod extending to the tail, couldn’t handle its loads in the air during turns and other maneuvers, so it would snap, explained aerospace engineering student Shreya Chandramouli, the team’s aerodynamics and structures lead that season. “The tail and the wing would just detach, and it would crash,” Chandramouli said.

“We fixed that in the final plane by putting a lot of structure around the boom, where the connection is between the tail and the wing, so there would’ve been no issues with it trying to break, even with all of the loads it was handling,” Chandramouli said. “We were 90 percent confident we had the perfect plane.”

That was in March, just before spring break, and just before the COVID-pandemic halted university operations and drove teams out of their bays.

Many teams were wrapping up designs and preparing to compete as widespread shutdowns ensued. While adapting to cancelled and modified competitions, they waited to see what would happen next as universities and competition sponsors weighed ways to proceed in the fall. Would teams be able to hold onto designs amid cancelled competitions and use them in 2021? Would they start from scratch, but physically compete? Would they be asked to build at all?

Teams planned for all of the above and more. Design, Build, Fly named each of the group’s contingency plans: Plan Armstrong meant that the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics and its partners would go ahead with a standard competition and an in-person fly off. Plan Buzz meant that a physical competition would be nixed, but a virtual event would be on. “Plan Corona was if everything got cancelled,” said project manager Jack Barnes. “Basically, our plan for that was to fly remote-controlled airplanes against each other and call it a year.”

Student design teams deal with hundreds of snags and setbacks over the course of a single design cycle. They fix broken booms and faulty control systems in their remote-controlled planes. They address bolt tear-out in their steel bridges. They improve quality control for their concrete canoes. Since its onset, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented students with a host of new challenges for how they ideate, fabricate, test, compete, and work together. The response of many: Dig in when you can, and think beyond the one build when you can’t.

Summer 2020: Distance design learning

Design, Build, Fly was among the teams that saw their physical competitions cancelled in spring 2020. That season, DBF teams were scored solely on their design reports. “I was devastated for a bit, because we couldn’t see the plane fly,” said Chandramouli. “That was only a little part of it. I think the bigger part for me was the fun of competition and the fun having the team all together. I’ve been with the team for so long, and some of the team members that I’ve met and become best friends with throughout the past four years — we didn’t realize the week before would’ve been the last time we were all in the same bay together, building the plane.”

In a normal competition year, coming back from the national Design, Build, Fly competition marks a time of transition. Outgoing members transfer knowledge to current and new members, and new team leads step into their roles. The team reflects on how the competition and design cycle played out. Taking place early in the pandemic, the post-competition transition had more urgency to it.

With the team scattered for the foreseeable future, new leads had to figure out how to transfer knowledge, keep the group organized and talking remotely, and navigate the uncertainty of the next year. They wouldn’t learn how the next competition year would move forward until September. “We had to do more work over the summer than in previous years,” Barnes said. “We never had a set-in-stone training program for our teams.”

Barnes became the team's project manager and worked on summer plans with Shreya Chandramouli, who became the team’s chief engineer. In addition to developing Plans Armstrong, Buzz, and Corona, the team’s priorities for the summer were to learn and bond, Chandramouli said. She and Barnes created design exercises in which new propulsion, manufacturing, electronics, and other leads looked at rules and reports from previous design years and went through how they’d design an aircraft.

“They got that experience: ‘Based on my knowledge, how can I best build an aircraft to do this task?’” said Barnes. “We just did it over Zoom, and they really got into it and wanted to learn more. Throughout that summer itinerary, it was really cool to see our new leads step up and fill those shoes of our former leads.”

Barnes also started a weekly webinar called Lead Spotlights. “We would have the lead talk about anything they wanted to talk about, but we wanted it a little bit more toward what their lead position was,” Barnes said. “They did research and learned a little bit more about their position and what it looks like after college. So, it was not only about the leads feeling comfortable communicating and teaching an idea to other people — especially in front of a group — but having them learn more about their role.”

Aside from using summer downtime for distance learning, Chandramouli wanted to give members time to connect. “We’d spend about an hour every few weeks just chatting about our summer and keeping it very casual,” Chandramouli said. “It’s been a stressful time. A lot of people’s internships got cancelled, stuff like that. We understood that people were just not in good situations. So DBF, I was just hoping it would be the light of the summer.”

Chandramouli wanted to give members time to connect. “We’d spend about an hour every few weeks just chatting about our summer and keeping it very casual.”

Robin Ott, an associate professor of practice and the mechanical engineering department's senior design program coordinator, echoed the need to lend support in a stressful time. Ott worked with more than 400 mechanical engineering students on senior design in 2020, and when design team members working on their final projects could no longer stay on campus, she worked to reformat their final deliverables.

“It was about finding that balance for them that could maintain the high quality of education we typically deliver, while also respecting the difficulties the students are experiencing in their lives during the pandemic,” Ott said.

Fall 2020: New rules

By fall, the competition rules from the Society of Automotive Engineers were out: The tentative plan was to use a hybrid model with virtual “knowledge” events and in-person “validation” events, the latter giving teams a space to operate their vehicles and have them receive technical inspection, with new rules developed by SAE for COVID-19 safety.

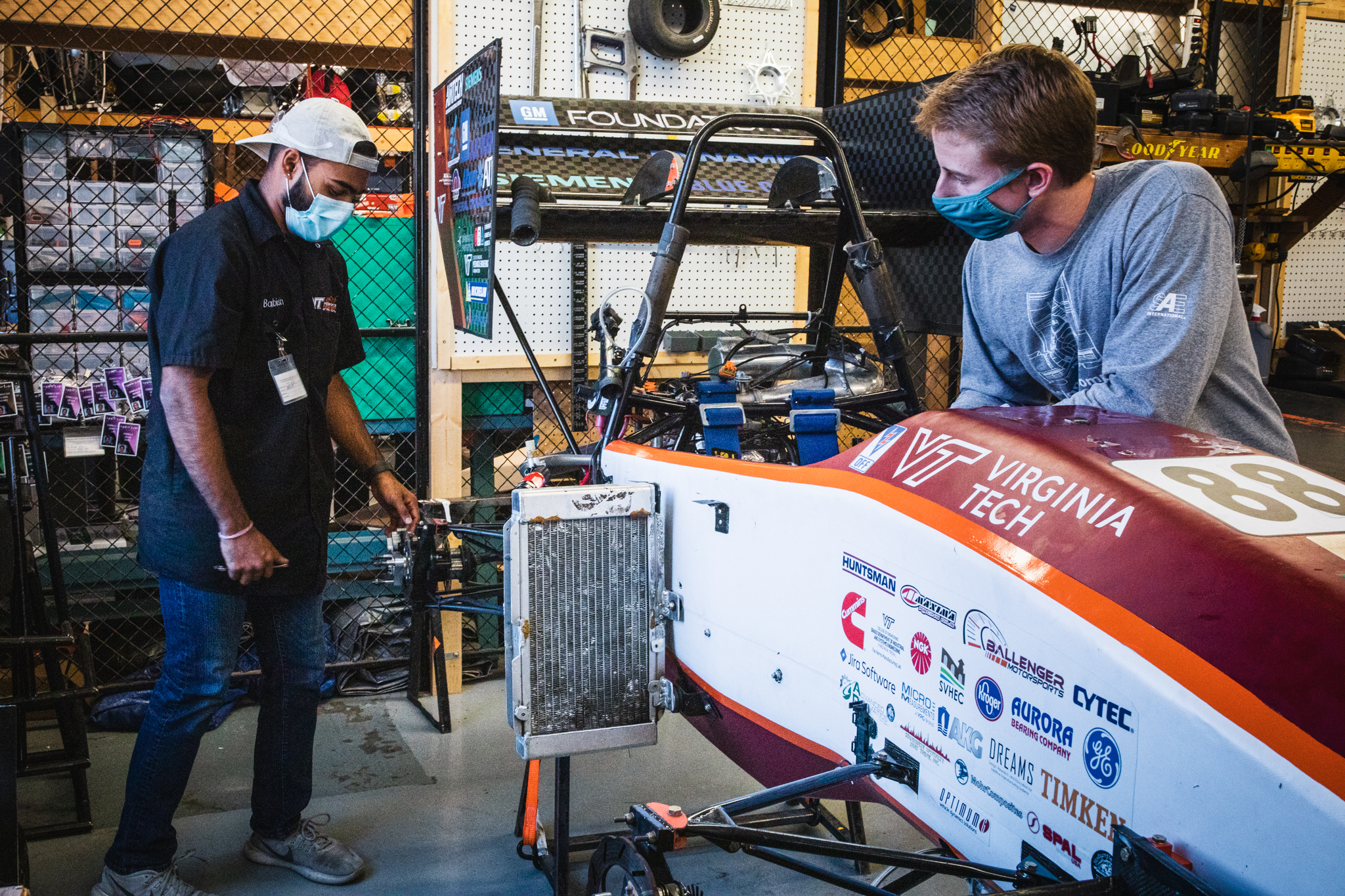

Virginia Tech’s Formula SAE team designs two formula-style vehicles — one with an internal combustion engine and the other with a fully electric powertrain. As the new rules were released, the group learned they would be able to carry their spring 2020 designs into the next school year.

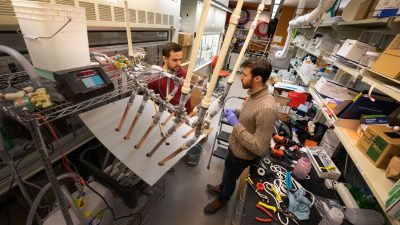

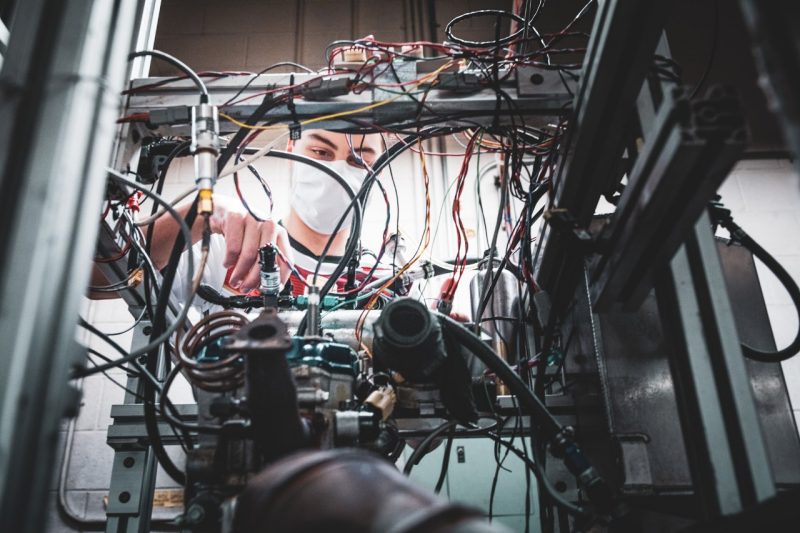

Formula SAE’s electric vehicle group was in the middle of manufacturing when the team’s spring design season was cut short, remembers power team lead and electrical engineering student Adam Yi. In carrying their designs over to the spring 2021 competition, the team was able to plan to finish manufacturing in fall and dedicate the full spring season to testing. That fall, the team came back to the Ware Lab with new conditions for working safely on their designs.

Over the summer, lab manager Dewey Spangler had drawn up new protocols for teams returning to work in the Ware Lab, a 10,000-square-foot design space with 500 students signed up to use it when the pandemic hit. While the Ware Lab was closed, Spangler worked with shop manager Philip Ratcliffe to install plexiglass partitions in lab spaces. As teams trickled back into the lab, they had to adhere to rules including limited capacity – four to six students max in each lab space at a time – six-foot distancing, mask-wearing at all times, disinfection of spaces, and self-quarantine and testing protocols for potential exposures.

"These strict protocols are necessary to ensure that students and staff have a safe place to work," Spangler said. "Limiting bay capacity and the ability of students to interact has been a hardship due to the nature of the work done in the lab — it's hard to construct a Baja off-road racer while staying six feet apart — but students have complied well with the restrictions."

Formula SAE has taken the protocols seriously, Yi said. “We make sure to keep everyone on the team accountable,” he said. “It’s slowed down our pace, but we want to make sure everyone is safe, no one is at risk, and that we’re following all of the guidelines.”

Yi has felt a sense of determination among current team members to stay in the lab and finish the cars. “We owe it to the previous seniors that were working on this car,” Yi said. “They put so much work and hours into designing it. We feel responsible to make sure that they get to see this car actually run and move.”

Spring 2021: Next generation goals

At the start of fall 2020, Virginia Tech’s Concrete Canoe team learned that the 2021 concrete canoe competition hosted by the American Society of Civil Engineers would be virtual, removing construction of a physical prototype and ending design at a theoretical point. After the cancellation of the spring 2020 competition, it was tough to take, said Jessica Viehman, a civil and environmental engineering student and one of the team’s current captains.

“There were tears,” Viehman said. What to do next has been a matter of perspective. To her, there’s more to being on the team than any single design cycle or competition outcome. Now, Viehman and her co-captains are equally focused on what they’ll leave behind for their team.

“My standpoint, being a senior, is: I think the most important thing is preparing the next wave of leadership,” she said. “This year, I have no expectation for the competition, in terms of our results. Of course, I want us to perform as well as we possibly can and to do our best, but I think ensuring that there’s longevity in the team is the most important thing right now. The focus has really been on trying to get new members involved in an online setting, drawing people into the team, and preparing next year’s leadership for hopefully assuming normal operations.”

Viehman’s focus on the group's future stems from a love for the team built up over the four years she’s spent as a member, working with teammates who share her passion for the challenge of designing a lightweight, 20-foot-long concrete canoe per changing specs, using concrete they’ve mixed and poured themselves. “If you had to ask me what was the best part of my experience at Virginia Tech, I would hands down say the concrete canoe team,” Viehman said.

A few memories stand out: Helpful advice from upperclassmen on car rides to competitions. A long work session in which she and a co-captain dusted off a five-pound bag of gummy bears. “Laughing, getting messy,” Viehman said. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had concrete in my hair. Last year, we constructed a green canoe, and I had green hands for weeks. My teammates jokingly called me ‘The Incredible Hulk.’ Over the years, I've made so many fun memories with the team that don't relate to engineering. I'm so thankful for the friends I've made, whom I would never have met if I hadn’t joined the team."

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had concrete in my hair. Last year, we constructed a green canoe, and I had green hands for weeks. My teammates jokingly called me ‘The Incredible Hulk.’"

Other design team members share the feeling — that their experiences are shaped by much more than their ability to compete in ways they’re used to. For Adam Yi, there’s the satisfaction of building a race car. “It kind of becomes your little kid, because you really want to see it go,” Yi said. “You’ve put in so much time and commitment beforehand, and you want to see it work.”

There’s also something to seeing concepts made real, he said. Yi had read about 100 amps or volts as powerful currents, but in working on Formula SAE's electric vehicle, he found a physical reference for it. “You know that 100 amps would be ridiculous,” Yi said. “A lot of electrical engineering is conceptual. It’s kind of hard to visualize electrons moving through a wire. Working on a design team, you get a feel for the things they’re talking about. We deal with physical aspects like temperature, costs, weight, max ratings, and working within larger systems, which need to be taken into account when making the circuit for real."

John Zeglarski, a civil and environmental engineering student and the captain of the Steel Bridge team, feels the same way. Each year, the team designs a steel bridge that weighs a couple hundred pounds and sustains a couple thousand. Members assemble it with a time limit in competition.

“This was a great team to get hands-on experience and real world knowledge,” Zeglarski said. “You can see your bridge in action. You can see how it deflects. When they say, ‘when you load your bridge with two kips, you’re going to get a quarter of an inch deflection here’ — that’s very abstract. You’ll learn that in a classroom and you’ll be able to run those calculations. But I don’t know what ‘two kips’ means, I don’t know what ‘a quarter of an inch deflection’ means. When you see it in front of you, you develop that understanding. My ability to understand a bridge, talk about it — what a kip here, a kip there means, what different types of torque moments and shear forces will cause — I’ve been able to refine that and see that in person.”

Like Formula SAE, the Steel Bridge team was able to carry its spring 2020 design over, but in December, the American Society of Civil Engineers moved its 2021 competition to a virtual format. Though the team won’t compete in person, it’ll be fulfilling to see the finished bridge stand, Zeglarski said.

“It’s exciting seeing the bridge,” Zeglarski said. “We’ll see what everyone worked on. We’ll be able to load it ourselves, and we’ll be able to show: This is a bridge that weighs 200 pounds and bears 2,500 pounds. This is something that we all worked on together. You can stand on it, you can walk on it. 2,500 pounds is the weight of a small car — it’s a sturdy design. And it’ll be really cool to see that.”

For spring 2021, Design, Build, Fly has built an unmanned aerial vehicle sensor drone, acting on Plan Buzz with a virtual competition. While working on the design, Chandramouli accepted a job offer from the Sierra Nevada Corporation as a flight test engineer. It’s her dream job, a mix of working on avionics systems in the office, on manufacturing in the shop, and on tests in the air.

She looks back at her last year with Design, Build, Fly, as well as those before it, with more faith in herself. “One of the biggest things I personally have taken away from this organization, that I know will be useful for me in the future, is the leadership skills I’ve gained,” Chandramouli said. “I think I’ve grown in terms of being a sophomore, a member on sub-teams, then becoming a sub-lead, and then another sub-lead, and then chief engineer. It was a wonderful progression of how to deal with teams, how to deal with people under you, but also above you, and how to increase that communication. Can’t say I’ve perfected it, but I’ve learned a lot, especially this past year.”

Photos by Peter Means, Video by Spencer Roberts

If you want to have an impact on our students and faculty like those featured in this magazine, go here to support the College of Engineering. For more information, call (540) 231-3628.

-

Article Item

-

Article Item