Virginia Tech engineers lead an EPA-funded effort that taps a growing crowd of consumers who want to learn how to better protect themselves from lead.

The community Johnson has served as a minister of the Gethsemane Lutheran Church in Cicero since 1981 are her people—her world—along with her canine companion, Rex.

Johnson’s parsonage was built sometime after 1920, complete with lead pipes. Back then, much of Cicero was an airfield before it became a neighborhood.

“I didn’t know that I had lead pipes until last year,” said Johnson.

In Chicago’s suburbs, including Cicero, Berwyn, and Robbins, lead service pipes are prevalent—totaling hundreds of thousands of networks of pipes. Most U.S. homeowners own the infrastructure from the property line to their home and the city or town owns the pipes from the property line to the water main.

Unfortunately, like many of her neighbors, Johnson’s pipes are galvanized iron at the property line and then transition to lead as they reach the foundation of her home. She would need to spend as much as $10,000 to replace all of the antiquated piping that leaches lead into her tap water.

One temporary remediation strategy to clear the lead from Johnson’s drinking water is to continuously flush, every day, allowing the water to run for more than 20 to 30 minutes, or the time it takes to run one load of laundry.

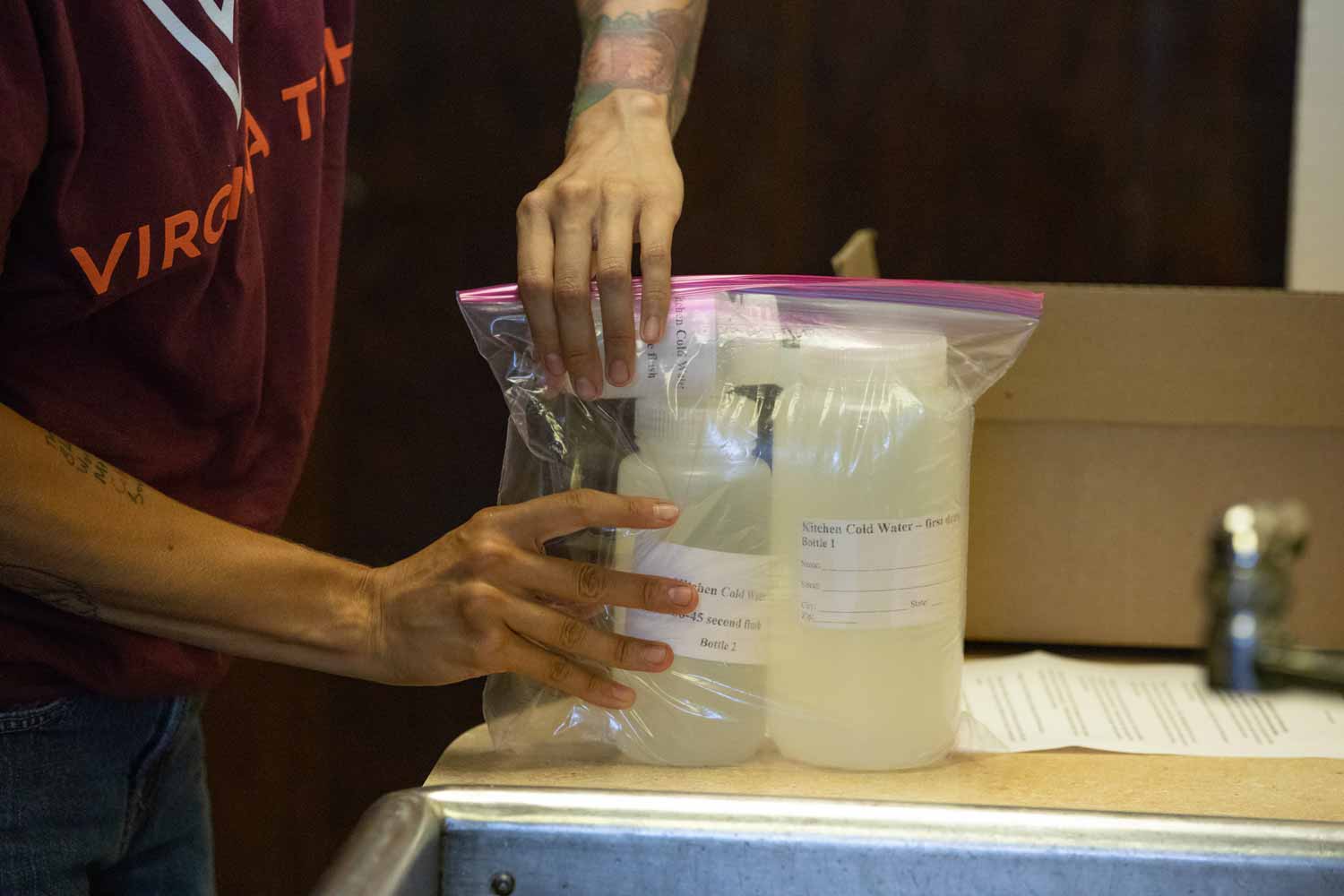

“If you are taking a daily bath or using your garden hose every week, then we compare your results to those who aren’t using their water at all,” said Siddhartha “Sid” Roy, Virginia Tech post-doctoral researcher.

Initial profiling sampling—where 20 or more one-liter samples are taken consecutively from the tap—in some Cicero and Berwyn homes showed that after 10 minutes of flushing, lead was still prevalent, reflecting a persistent lead-in-water problem that was not revealed in the state-sanctioned testing. The highest lead level detected was at the kitchen tap in Johnson’s church—28 times the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s maximum allowable level of lead in bottled water.

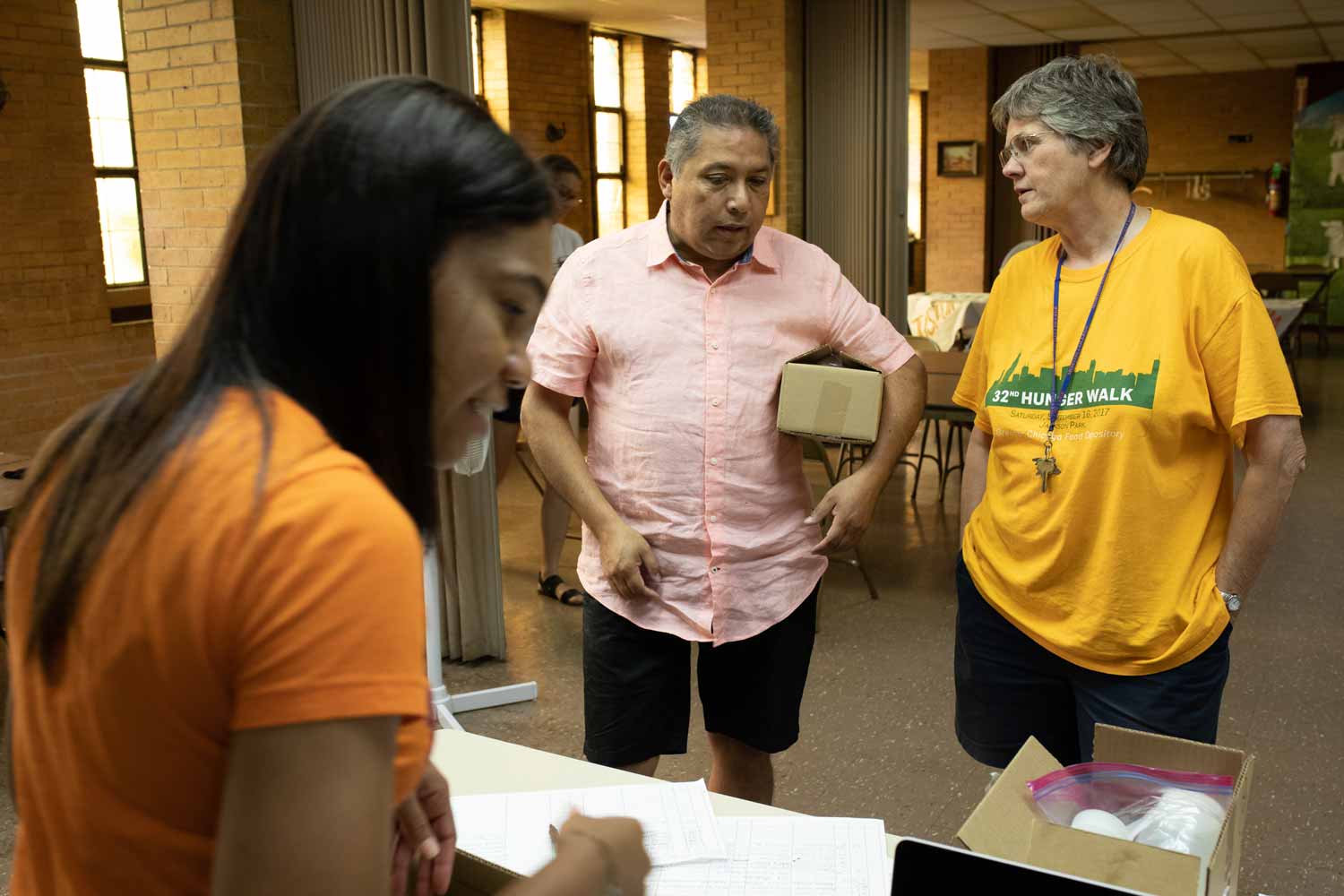

More than 100 three-bottle water-testing kits—the same kind used in Flint, Michigan—were distributed in Cicero and Berwyn. Results showed that 1 in 3 households tested in both towns had concerning lead concentrations.

The federal law, called the Lead and Copper Rule, requires that if 90 percent of homes tested in a city are below 15 parts per billion, the city is in compliance. While the first draw 90th percentile lead levels in Cicero and Berwyn were below 15 ppb and met the much-criticized law, lead in the flushed samples, referred to as second and third draws, did not drop, but stayed above the FDA standard and sometimes even increased.

Flushing alone would not adequately reduce lead exposure risk from Cicero and Berwyn water.

“So now we drink filtered water out of this pitcher,” said Johnson as she filled a conventional water pitcher which has a built-in filter. Her kitchen sink faucet does not have the part needed to attach a $30 water filter that residents are encouraged to buy to minimize the impacts of lead.

A hotbed of lead pipes

Ixchel, a community activist group founded by Cicero and Berwyn residents two years ago to bring social awareness to such hazards, first began testing the community’s water with Virginia Tech in 2017. Rev. Johnson, who co-founded Ixchel with Delia Barajas, sounded the alarm after dirty particles in her kitchen water made her skeptical of public officials saying their water was safe.

Johnson and Barajas meticulously compared Virginia Tech’s water-testing instructions with those that the city had provided, uncovering that the city’s instructions were erroneous and that following them could yield lead levels much lower than the real levels. Johnson had read about the Virginia Tech researchers that had come to Flint’s aid, and so she sought them out.

Roy, along with other Virginia Tech researchers, responded immediately, knowing that the outlying Chicago suburbs, as well as the Windy City, “are [a] hotbed of lead pipes in the U.S.,” said Roy.

Roy has worked alongside the Virginia Tech water study team since 2015 when the Flint water crisis broke, so he refers to Flint when explaining how bad science and unethical decisions by scientists and engineers can result in societal harm. By working in places like Chicago, Roy seeks to prevent and reverse that damage, which validates his passion to bring together a community of advocates, hence broadening the ripple effect.

Together empowered

Experts now say that 844 million people live without access to safe water. How will engineers, scientists, policymakers, and citizen advocates work together to mitigate this growing national epidemic?

In spring 2018, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency awarded $1.9 million to Virginia Tech, North Carolina State University, the University of Iowa, Louisiana State University, and Texas A&M to uncover, detect, and control lead in drinking water.

“There are three specific case studies that this grant focuses on,” said Kelsey Pieper, Virginia Tech research scientist. “Michigan residents because the state is implementing a more ambitious rule with consumer-centric elements, private well owners who are 100 percent responsible for detecting and controlling water lead risks, and residents protected by the existing Lead and Copper Rule, but live under circumstances that historically make compliance difficult to achieve.” Chicago suburbs fall under the latter of the three case studies.

By working directly with consumers and citizen scientists over the next three years, the EPA-funded project is designed to increase public awareness of lead in water and plumbing on a national scale.

“We are tapping a growing ‘crowd’ of consumers who want to learn how to better protect themselves from lead, and in the process, create new knowledge to protect others,” said Marc Edwards, University Distinguished Professor, explaining how citizen scientists come to fruition.

Together, Edwards, Roy, and Pieper, plus a collaborative team of university engineers and scientists, have been uniting one of the largest citizen science engineering projects in U.S. history. The end goal: To help individuals, like Johnson, and communities, like Cicero and Berwyn, deal with the shared responsibility for controlling exposure to lead in drinking water through a combination of low-cost sampling, outreach, direct collaboration, and modeling.

Long before the Cicero sampling project or the Flint water crisis, there was the Washington, D.C., water crisis that began in 2000 and spanned four years, ending with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention admitting it had misled the public about the risk of lead in the District's drinking water.

But because of Flint, not D.C., Edwards said citizen scientists seem to have become more empowered and the public and media have paid more attention to water issues. The door has opened for consumers and activist groups, like Ixchel, who want to learn how to better protect themselves.

Whether from wells or municipalities, we all consume water and can collectively work together to reduce health risks, said Edwards.

The choice of life

Making sure basic needs like air, food, shelter, and water are taken care of is not something Chivonne Battle takes for granted.

For Battle, unveiling the truth in Cicero and Berwyn is personal. Growing up as a person of color in an impoverished environment, “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness were not spoken to, or for, me,” she said. The desire to protect the most vulnerable stems from her personal experience with poverty.

“I was only exposed to happiness as defined by the government: canned peanut butter, cheese blocks, and powdered milk—all of which was shared with unwelcomed multi-legged friends,” said Battle. “In poverty, you do not get to choose life, it is chosen for you.”

Through sheer determination, Battle built a better life for herself through the power of education. Now, a two-time Hokie with degrees in materials science engineering and working toward her doctorate in planning, governance, and globalization in the School of Public and International Affairs, Battle fully comprehends what advocacy and persistence truly mean.

“Because there were communities that may not have known … I have literally been able to go under bridges, you know, that most people don’t cross, and simply pull up next to someone’s house and say, ‘Hey, do you know what the lead levels are in your drinking water?” Battle said about how she's reached different groups of people.

This past summer, as part of the EPA-grant with Roy, Pieper, and Edwards, Battle worked one-on-one with Chicago residents to rectify social injustices. Her doctoral study is to “research and develop a way to reverse the physiological and psychological impact of socio-economic despair.” In essence, Battle hopes her work can reverse poverty while pursuing the truth.

Battle sees the current water problems in the three Chicago neighborhoods as her chance to help the voiceless. It’s also how she came to meet Robert Thamm, resident of Cicero and a retired chef whose upbringing was similar to Battle’s living under impoverished conditions.

Thamm was unaware of the potential exposure to lead in his drinking water. But, Battle was able to reach him by simply responding to his request for a testing kit to be delivered to his front door. Thamm graciously invited her into his home so that she could examine his kitchen faucet to see what kind of filter he needed.

“Robert made my day. Because they (residents) remind you why you do this,” Battle said.

One by one, Battle takes her time with residents, visiting them in their bungalow row homes, collecting test kits, and asking about filters.

“You have a lot of vultures that come out here and try to sell residents $2,000 filtration systems that they don’t need,” Battle said, shaking her head. “A lot of times, you have communities, small communities like this, they unfortunately are overlooked or taken advantage of.”

Battle explained that without the right information and education, choices are made for residents that are poisoning their mind and body.

“Reversing this notion is important to me,” said Battle. “Impoverished communities are not always afforded the tools or truths to choose. All human beings should have the choice of life. And I just want to do my part to keep that going.”

Photos by Peter Means

An aging, taxed infrastructure

Today, U.S. water utilities continue to confront a number of major challenges. As demands on the aging pipeline infrastructure increase across the nation, so does the prevalent issue of lead-in-water at the tap — only one among many problems that have left regions facing water-related challenges.

Drinking water in the United States is delivered through 2 million miles of pipes with many of those pipes dating to the early to mid-20th century with a lifespan of 75 to 100 years. Drought, flooding, and population growth also strain infrastructure systems that have been neglected and failing at unacceptable rates. Results of a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency survey show that $384 billion in improvements are needed for the nation’s drinking water infrastructure and $271 billion to maintain and improve the nation’s wastewater infrastructure systems.

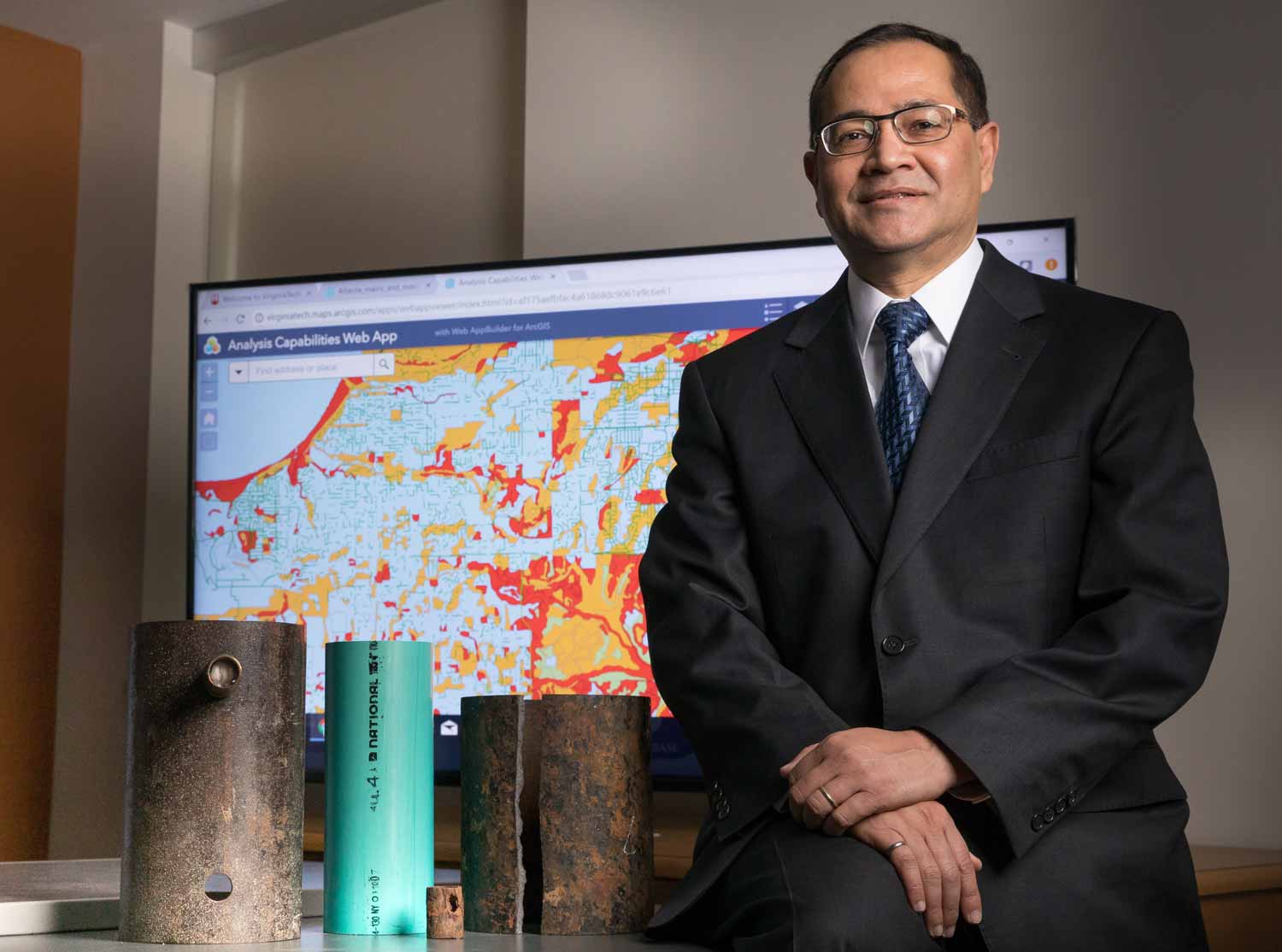

To answer this challenge, Sunil Sinha, professor of civil and environmental engineering, along with his student researchers, is leading a U.S. Bureau of Reclamation-funded effort named PIPEiD, also known as Pipeline Infrastructure Database, to collect data on the reliability of the nation's aging water pipelines and then establish an infrastructure database for resilient and sustainable water systems.

“Since we announced this project in early 2018, we’ve had more than 150 water utilities across the country participate,” said Sinha. “Most of the top 25 cities, based on population, in the United States are now participating in the project, including American Water, the private water utility, which serves 15 million people and operates in 46 different states.”

As part of supporting Virginia Tech’s land-grant mission, Sinha’s team is also partnering with the Virginia Department of Health to engage small water utilities in Virginia, in addition to several state agencies.

Over the course of the next five years, the Virginia Tech team of researchers will collect high-quality field performance data on reliability for water pipelines of different materials, including cast iron, ductile iron, reinforced concrete, steel, lead, plastic, thermoplastic, and others. This study will include analyses of the economics, cost-effectiveness, and life-cycle costs associated with the various water pipe materials under evaluation.

Video by Erica Corder, Photos by Peter Means

If you want to have an impact on our students and faculty like those featured in this magazine, go here to support the College of Engineering. For more information, call (540) 231-3628.

-

Article Item

The future of farming , article

The future of farming , articleSpurred by a graying workforce, Virginia Tech researchers are laying the groundwork for an accessible future of agriculture.

-

Article Item

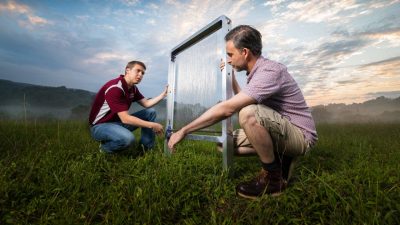

Out of the lab, into the field , article

Out of the lab, into the field , articleWhile traditional fog harvesters use mesh netting to catch these droplets, the fog harp opts for a vertical array of wires instead, a design change that increases their collection capacity for clean water by threefold.

-

Article Item

Full speed ahead , article

Full speed ahead , articleFrom planes to cars, there’s no stopping 25 year-old alumna Paige Kassalen, who made history with the world’s first solar-powered flight.