Alumni are helping Virginia Tech establish a lab that aims to be a leading international vibrations research lab.

When you buy a mobile phone, you might not think about how far it’s traveled to get to your pocket. You might think even less about the vibrational forces that acted upon it during its journey to you.

But in the Advanced Vibrations and Acoustics Lab (AVAL), founded and directed by mechanical engineering professor Pablo Tarazaga, researchers are poised to make important inroads into determining standards of just how much vibration an object can take, including objects like your phone.

Sriram Malladi continues to work in the lab as a postdoctoral researcher since earning his master’s degree and Ph.D. in mechanical engineering from Virginia Tech. He says he was drawn to researching vibrations because it’s one of the most ubiquitous forces in our daily lives — which means most of us forget about it.

But not in the lab where certifying the structural integrity of objects from cell phones to car parts to military equipment takes prominence. And with the help of alumni who work at the U.S. Naval Surface Warfare Center at Dahlgren, the lab was loaned new equipment that enables further research capabilities.

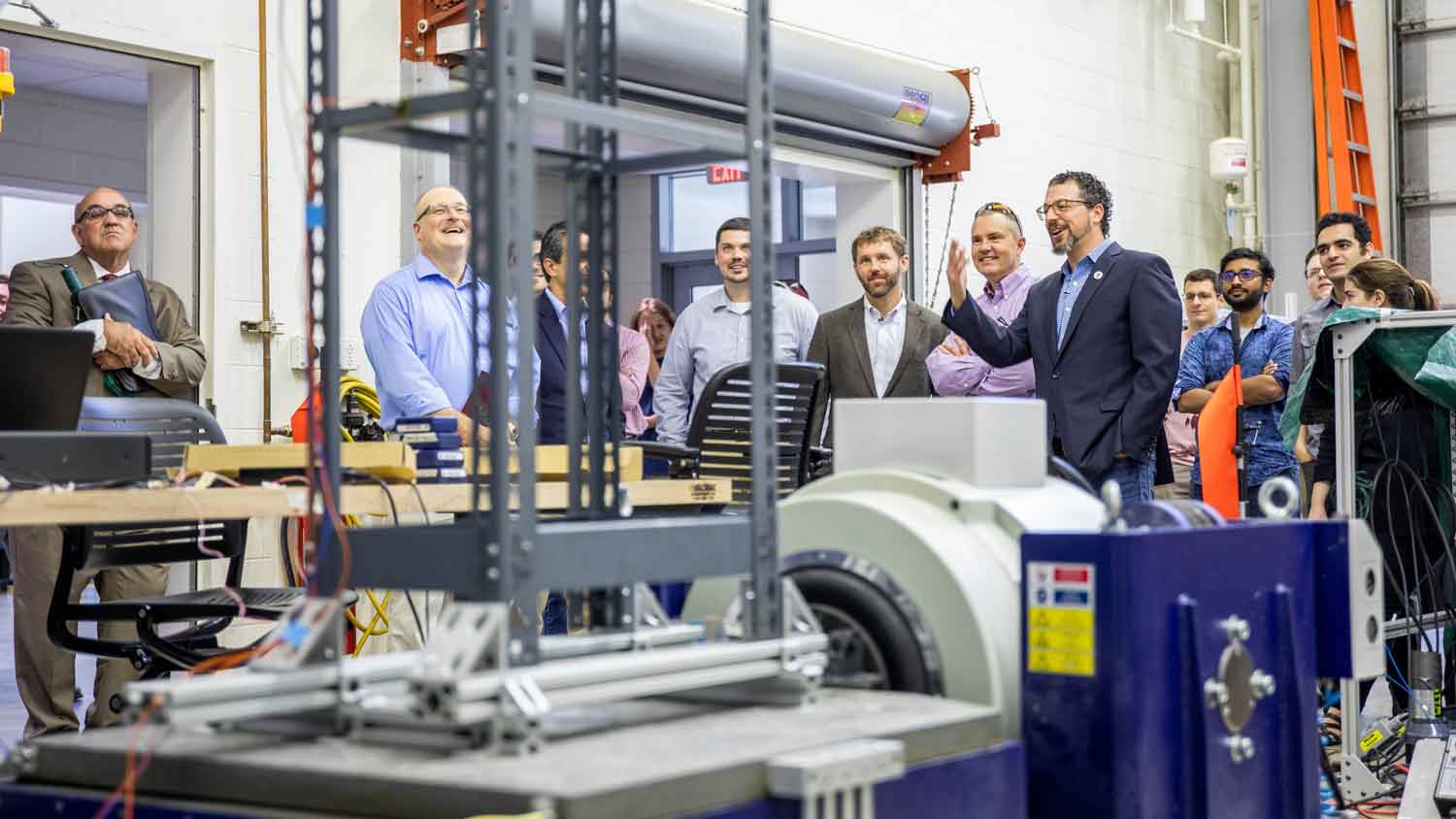

In December 2017, Tarazaga and Malladi watched as a crew unloaded a 2,000-pound, navy blue shaker table and its components into AVAL’s first floor space in Durham Hall. The shaker table, which can apply a vibrational force of up to 2,000 kilograms, can shake objects at frequencies as high as 4,000 hertz — meaning the researchers can recreate a wide array of environmental conditions in the lab like those seen in the field.

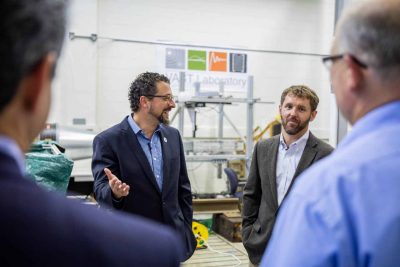

The loan was orchestrated by alumni who work at the Naval Surface Warfare Center at Dahlgren, including shock and vibration technical expert Luke Martin (M.S. in mechanical engineering ’04, Ph.D. in mechanical engineering ’11), who was classmates with Tarazaga.

“We use shakers as a tool in our field to basically qualify equipment in weapon systems to go out in the fleet, and this was a shaker that we had that we really weren’t using,” Martin said. “So we thought under our educational partnering agreement with Virginia Tech that we can essentially loan it down to Virginia Tech indefinitely, and they can get really good use out of it.”

Not only does the equipment expand the lab’s research capabilities, the partnership signals progress in a plan to ultimately create a vibrations and adaptive structures consortium among Virginia Tech, other universities, government, and industry — a consortium Tarazaga and the other involved College of Engineering faculty hope to base out of the Blacksburg campus.

If it pans out, Malladi explained, it will position Virginia Tech to play a central role in an ongoing movement to develop international standards of environmental testing. Currently, objects are certified by demonstrating how much vibrational force they can take until they break. But the hope is to develop a certification framework that can assist in the design stage when creating objects and to better understand the forces acting upon objects in transport and field operation.

For the Navy, that could help with ensuring the safety of any equipment deploying onboard a ship. One day, it could even help when designing rockets and onboard components, which are subjected to extreme vibrational forces. And for the rest of us, it might mean our fragile phones are shipped with a little more care, so they arrive as pristine as when they were manufactured.

Photos by Erica Corder, video by Jack Beach.

If you want to have an impact on our students and faculty like those featured in this magazine, go here to support the College of Engineering. For more information, call (540) 231-3628.

-

Article Item

-

Article Item

-

Article Item