Alumni and faculty said a final goodbye to Randolph Hall during Homecoming Weekend.

In 1959, Virginia Tech was tight on space due to its largest enrollment since the post-World War II boom. Throughout the 50s, the university's growth had steadily increased, reaching over 5,000 students. Adding Randolph Hall to the Blacksburg campus provided much-needed space for engineering students to learn, as well as a home to the chemical engineering and the aerospace and ocean engineering departments.

Named after Lingan Strother Randolph, professor of mechanical engineering, head of the mechanical engineering department, and dean of engineering from 1893 to 1918, Randolph Hall was constructed in two sections completed in 1952 and 1959.

Three years after the first section was completed, Jane Johnston began working as the department head’s secretary, using a manual typewriter to type students’ theses and a hand-cranked copy machine. After being employed in Randolph Hall for 68 years, Johnston, the program support technician for aerospace and ocean engineering, has witnessed many changes from the name of the department, formerly the Department of Aeronautical Engineering, to the addition of the building and more than eight department head transitions. However, the one thing that will always stay with her is the love she had for giving advice to students and working with the faculty, staff, and researchers.

“My offices have changed, but I have found my home in Randolph Hall my entire time here."

—Jane Johnston

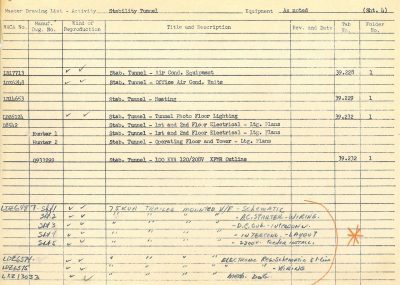

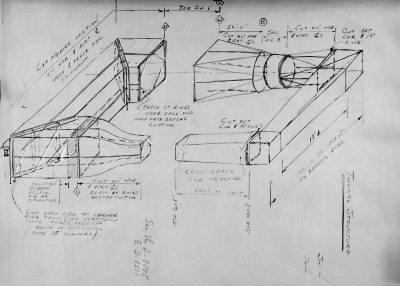

The historic building has been the home of research spaces like the Stability Wind Tunnel, acquired from NASA in 1958. The wind tunnel made its way to Blacksburg from Langley Field in 60 trailer trucks. Its installation helped place aerospace and ocean engineering above its peers along the East Coast by training students and researching aerodynamics and aircraft design. The new Mitchell Hall will be constructed around the wind tunnel to provide more modern spaces and resources while maintaining the integrity of this iconic experiential research space.

Structure and materials researcher Rakesh K. Kapania, a 38-year faculty member and Mitchell Professor of Aerospace Ocean Engineering, said his earliest memory of Randolph Hall is walking through its corridors and running into some of the giants in aerospace engineering research — the likes of the late Hank Kelly, the late Raphael Haftka, Roger Simpson, and Gene Cliff. Their expertise spanned from mastery in control theory, optimization methodology, aerodynamics and hydrodynamics, as well as dynamics and control.

“Randolph Hall is the place where Joseph A. Schetz, the Fred. D. Durham Endowed Chair in the Kevin T. Crofton Department of Aerospace and Ocean Engineering from 1969 to 1993, transformed a small aerospace engineering department into one of the finest institutes of higher learning in aerospace engineering,” said Kapania.

Original laboratories in the building included the trans-sonic and supersonic labs, the aircraft instrument and aircraft structures labs, the machinery room, and the chemical engineering unit operations lab. Most of these researchers have outgrown the space and relocated, although the supersonic lab has since been decommissioned. Labs that remained in Randolph Hall until the move to prepare for demolition include the aerospace structures and materials laboratory, experimental aeroacoustics laboratory, and the hydro-elasticity laboratory, among others.

When people weren’t running into research greats in the halls, alumni and faculty remember walking through its narrow corridors that were only made more limited by the students sitting along both walls working on their laptops between classes.

Reminiscing on Randolph Hall

As a hub for engineering classes, the Frith First-Year Maker Space, senior design project space, and research labs, thousands of engineering alumni have made memories in Randolph Hall. Step into the shoes of a handful of alumni who shared their stories during Homecoming Weekend:

Richard (Dick) Ott

Class of ’61

Aerospace Engineering

Instead of taking the normal aeronautical laboratory course, the aerospace class of 1961 was given the honor of calibrating the wind tunnel that the school received from NASA Langley. Our first task was to chip off the ice accumulated on the wind tunnel from sitting in the mountains that winter. I’ll never forget the first time the wind tunnel was turned on — the glass observation window was sucked in, taking Department Head James B. Eades Jr.’s glasses with it.

Carolyn Bucklen

Class of ’75

Industrial Engineering and Operations Research

On the first day of my first engineering class in the fall of 1971, I walked into a classroom in Randolph Hall. All of the seats in the second row back were already occupied so I had no choice but to take a seat at the desk in the corner of the first row near the professor. This turned out to be quite fortuitous. After a few minutes of prep time, the professor said, “Take a look at those sitting around you — one of you will make it in engineering, and the other four will end up in business.” I noted to myself how fortunate I was to be one of the last students entering the classroom, occupying a corner seat — with no one in front or on one side of me — I already had this challenge half-licked. I did not allow his caution to intimidate me. I already knew I could do it.

In Orientation to Engineering 101, we read and discussed six essays. The final essay’s title was: “Should women be allowed to take up seats in engineering classrooms?” The premise was that by the time a woman was fully trained and productive, she would leave the workforce to start a family. This hit home because I was the only woman in my engineering classes. In 1971, 30 women started with me, but only six of us graduated with an engineering degree. When I graduated in 1975, there were fewer than 3,000 women engineering graduates in the whole country.

Jessica Greene

Class of ’04

Mechanical Engineering

As a mechanical engineering student, at times it felt like I lived in Randolph Hall — it was the place where my friends and I spent the most time. After I joined the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), we would hang out in its office in Randolph. The ASME office was a small place to get away and just chill when needed. I also remember looking up at the class pictures that hung in the hallways and knowing ours would be on that wall someday, too.

Tiasha Khan

Class of ’10

Aerospace Engineering

I made so many memories in Randolph Hall over the years, but my favorite was working on undergraduate research with Professor Craig Woolsey in the Nonlinear Systems Lab. The lab was a fun environment but fostered learning with many other students collaborating on interesting research. We designed a desktop model of a variable speed control moment gyroscope. Professor Woolsey is still using it as a teaching model today.

Michael Hazuda

Class of ’11

Aerospace Engineering

As an underclassman, I worked with a Ph.D. student in the student machine shop to build a model to use in the wind tunnel. We were able to spend the better part of a week working in the wind tunnel itself. I absolutely loved getting to control the wind tunnel and setting up our experiments that investigated limit cycle oscillations.

I spent much of my later years in Randolph. I remember walking by the Rankine bust in the main lobby to go spend time in the AOE lounge (with the cut-away of the propeller engine). I’d work on projects with my classmates or just rest on the couches in the lounge between classes.

“Randolph has been a longtime home for aerospace and ocean engineering, and other departments, but we are very fortunate to be getting a new state-of-the-art building. Mitchell Hall will be better suited to support our leading-edge research and teaching,” said Alumni Distinguished Professor William Devenport, who has been with the department since 1985 and has directed the wind tunnel for almost two decades. “In particular, we are excited and grateful that Mitchell Hall will be providing an amazing focus and vastly upgraded home for Virginia Tech’s internationally renowned Stability Wind Tunnel.”

With the help of a $35 million gift from Norris Mitchell ’58 and his wife, Wendy, construction of Mitchell Hall is planned for early 2024. The building will be more than 70 percent larger than Randolph Hall to help accommodate growth of the engineering programs and will accommodate for innovations in research and teaching. It will be an expanded, centralized hub for several engineering departments — including aerospace and ocean engineering, mechanical engineering, and chemical engineering, among others — thus, allowing for more interdisciplinary collaboration between faculty and students. Mitchell Hall will also be home to the Frith First-Year Maker Space.

If you want to have an impact on our students and faculty like those featured in this magazine, go here to support the College of Engineering. For more information, call (540) 231-3628.

-

Article Item

-

Article Item