Within a week of becoming friends, alumni Rob Wallace and Walter Barnes were making plans on future entrepreneurial ventures. Fifteen years later, they’re realizing the vision with a unique project in the clean energy sector.

Rob Wallace '00 and Walter Barnes '00 first met the summer before their freshman year at Virginia Tech, in 1996. Ask them to tell you how, and they both laugh.

“He used to rollerblade,” Barnes says.

“I still rollerblade,” Wallace interjects. “I went rollerblading last night.”

“He still rollerblades,” Barnes says, laughing. “Which I thought was very odd.”

That first summer, the pair adjusted together to college life early through a summer program called ASPIRE, now called Student Transition Engineering Program, run by the College of Engineering’s Center for the Enhancement of Engineering Diversity. They began to get to know each other over games of basketball and rounds of golf.

Within their first week of friendship, the pair were making plans together on future entrepreneurial ventures. Both of them wanted to own their own companies some day and both strongly believed in the same goals: “to be successful, bless God’s kingdom, and help people,” Wallace explained.

“I remember that first conversation, like, ‘Man, we’re going to start a company together one day,’ kind of thing,” said Barnes, who is a Grado Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering graduate. “It wasn’t even a question. And so, to have someone that kind of thought the same way and viewed the world the same way — because it is a perspective thing — is refreshing, and you know that you’re kind of in the battle together.”

In 2015, 19 years later, that battle became breaking the cycle of poverty, unemployment, and incarceration in Baltimore, Maryland.

In April that year, the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray, an African-American man from Baltimore who died from injuries sustained while in transit in a police vehicle, spurred days of protests in the city.

In the aftermath, Cherie Brooks, a real estate executive, felt compelled to bring something positive to her hometown of Baltimore. She jumped on a call with two like-minded locals: Wallace and Ray Lewis, a former linebacker for the Baltimore Ravens.

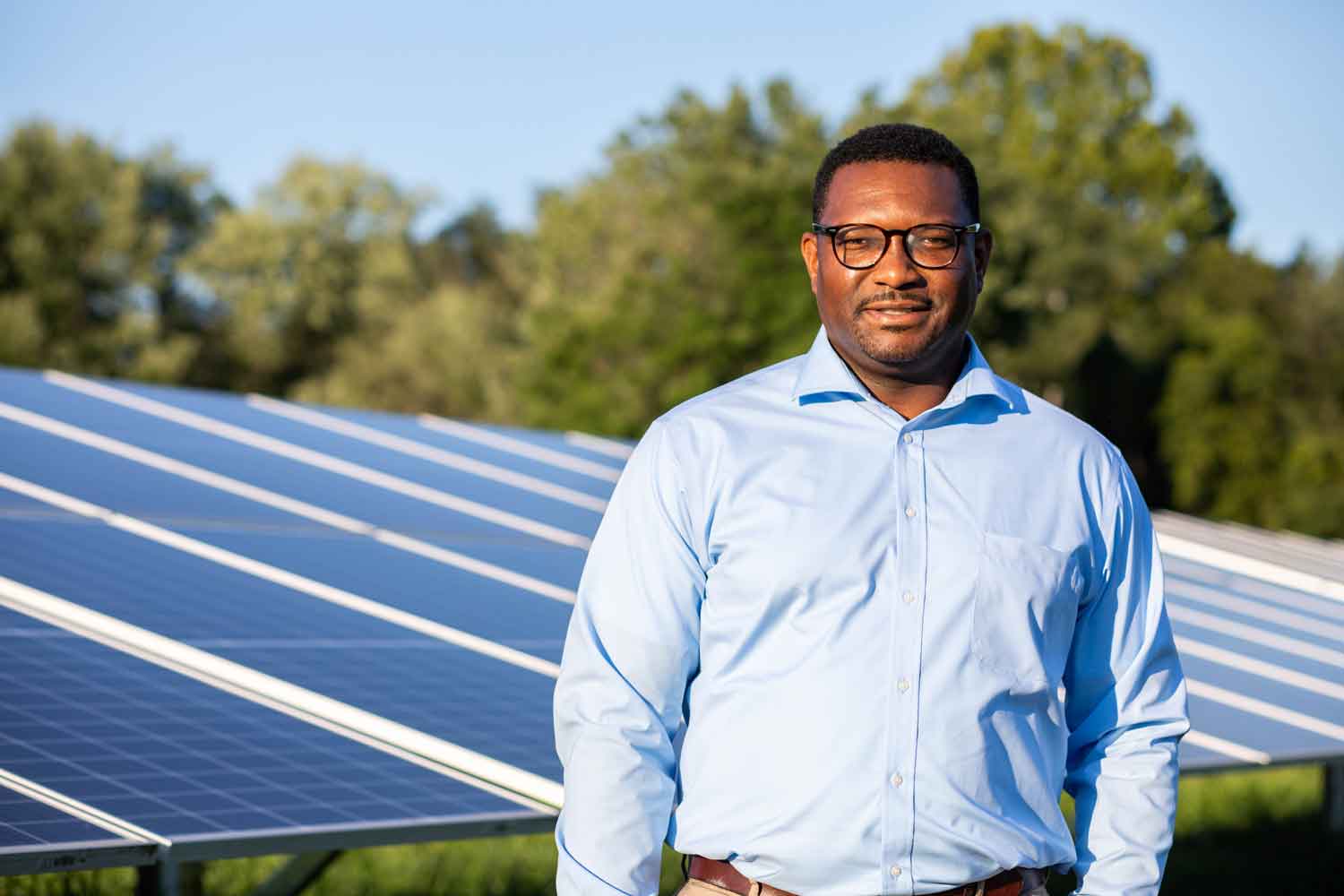

With Wallace’s expertise in solar energy development, the group came up with a plan to provide opportunities for community workforce development in the solar energy sector. So began the development of a company that would provide solar photovoltaic installation training and employment for at-risk adults, returning citizens, and underserved individuals living in Baltimore City and surrounding counties.

Over the course of several weeks, trainees learn to install solar panels on community and agricultural facilities and commercial rooftops, thereby driving further development of sustainable, clean energy in Maryland. Because of a global push toward renewable energy, the company’s technical education provides trainees with a valuable skill set in a growing industry. Meanwhile, the company’s focus on education in life skills like financial literacy make inroads in trainees’ lives outside of work.

A twofold mission like this is especially important in a city where nearly a quarter of residents live in poverty — about double the national average — according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

They decided to call the venture Power52 Foundation, which leverages Lewis’ football jersey number. But before they could move forward, Wallace and his co-founders needed a chairperson of the board for the foundation.

“I said, ‘Who is aligned with this mission, who do I trust with my life, and who has the same values that we have and is going to want to pour into people’s lives?” Wallace said. The answer was simple: “Walter Barnes.”

Barnes, who is president of PM Consulting Group and is also chair of another foundation started by fellow Hokie Eric King, admits initially he wasn’t sure he’d have time.

“But when your friends want you involved in something, — and I know him, he’s very passionate, I’m passionate — you make time for that. That’s important,” Barnes said.

So began a transformative company that has, to date, trained over 100 people of all backgrounds, giving them access to a better quality of life, and provided 30-megawatts of solar projects that will produce 40,000-megawatt hours of clean energy for 2,500 middle- and low-income households. For Wallace and Barnes, it’s been a rewarding three years.

“You couldn’t have planned it this way,” Wallace said.

As fortuitous as the complementary relationship between Barnes and Wallace may seem, they both agree the wheels were set in motion at Virginia Tech, through the efforts of the Center for the Enhancement of Engineering Diversity and its director, Bevlee Watford.

“You couldn’t have planned it this way.” -Rob Wallace

During the summer program Wallace and Barnes attended, they met dozens of other engineering students in an environment designed to effectively encourage a sense of camaraderie.

“You take that whole buffer out when you first come to college,” Wallace said, who graduated with a bachelor of science in electrical engineering. “When school started, we were already part of the family. So one of the things Dr. Watford did, which I think was critical for me, was she created an environment of partnership early.”

Both of them feel strongly that Watford and her guidance were crucial in their ultimate career and life success. Wallace said he often reminds Watford that without her, he wouldn’t be where he is today.

“It’s interesting how the university, Dr. Watford, and that whole program created this dynamic where they can take in kids from any background and bring them and we’re all starting here,” Barnes said, raising his hands up to show an even level.

For Barnes and Wallace, the ingredients for a strong relationship were already there in their personalities alone: Barnes, with his quiet resolve and reflective temperament, complements Wallace, whose charisma and boldness render him a perfect spokesperson for a company with an operating model so markedly unique. But the close-knit environment fostered by Watford’s vision just made it that much easier for the two to connect, they say.

Now, 22 years since the summer Wallace rolled into Barnes life, they’re known to each other's children as uncle. When they can, Wallace and Barnes like to come back to the place in the mountains where it all started. They even give back to Virginia Tech together, building an endowment that they hope will tackle issues of representation at the university by providing access to scholarships for more underrepresented students.

Their timing is advantageous: The 2017 installation of the new dean of the College of Engineering, Julia Ross, has ushered in a heightened focus on inclusion and diversity. Ross’ inclusive excellence vision actively prioritizes the recruitment and retention of students of all backgrounds, citing the need for every bright mind at the table to solve the transdisciplinary, complex problems of the 21st century.

The historic foundation and infrastructure laid by Watford’s leadership and through CEED allow for such advances — and it has since the days Wallace and Barnes first came to summer camp.

Irrespective of how far Wallace and Barnes have come since then, one thing remains the same. Just as he didn’t two decades ago, Barnes still doesn’t get the whole rollerblading thing.

“For the record, I’m not doing that,” Barnes says.

“Never. He wouldn’t even try,” Wallace says. “I had an extra pair.”

Photos and video by Erica Corder.

If you want to have an impact on our students and faculty like those featured in this magazine, go here to support the College of Engineering. For more information, call (540) 231-3628.

-

Article Item

-

Article Item