The Elon Musk-founded Boring Company aims to reinvent transportation by taking it underground, in high-speed networks of tunnel travel. In 2021, a Virginia Tech team took part in the company’s first-ever design competition, launched to inspire leaps in tunneling technology.

On day six of the Not-A-Boring Competition, the Diggeridoos watched the sun set on the Las Vegas Strip, less than a mile from the empty lot where the students were assembling their machine. They were close enough to the MGM Grand to feel the air around them begin to cool as the shadow cast by the hotel building, lit the green of a glowworm, lengthened over the lot.

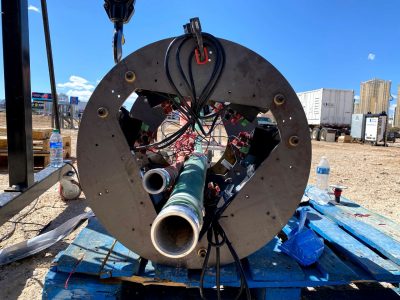

In the shade, the Diggeridoos could better focus on finishing their work on the Underdoge, a six-foot-long tunnel-boring machine propelled by four hydraulic pistons capable of producing 150,000 pounds of force — about five times the force from a Boeing 737 engine at take-off, said Taylor Ransford, the team's founder and chief engineer. The team designed the Underdoge for simplicity and speed using pipe-jacking, which keeps much of the machine’s infrastructure above ground and forces it forward with segments of pipe powered by hydraulics.

The Diggeridoos were one of 12 teams selected by the Boring Company from nearly 400 entrants to develop and demonstrate creative tunneling solutions at the company’s first international competition. Of the 12, eight made it to Vegas. They would spend the next six days in the desert assembling their machines and pushing through the rigor of industry-standard safety rules, in hopes of challenging a statement made by Boring Company president Steve Davis at the start of the week. Diggeridoos tunnel structures lead Austin Koontz remembered it: if any team had a working tunnel-boring machine and dug a tunnel by the end of the week, he’d be amazed.

As Davis foresaw, out of eight teams, only two would pass the competition’s 100-plus safety checks. Only one would dig, and none would dig a complete tunnel. The Boring Company put the teams up against problems the company itself had taken five years since its founding to solve.

That challenge was exciting to accept, whatever the outcome, Ransford said. “The main priority during the entire competition was to have fun,” he said. “That’s what we were there to do. It's a great learning opportunity, a great extracurricular, a great way to get hands on, but we always intended to have fun and do some cool stuff.”

Today’s tunneling practices would be too expensive and slow to produce the infrastructure needed to revolutionize transportation, according to Ransford. The Boring Company thus aims to disrupt the industry with lower-cost networks of tunnels that enable high-speed, driverless regional travel in such forms as Elon Musk’s Hyperloop. The Not-A-Boring Competition gave the company a way to source solutions with that disruptive potential “by getting a lot more people thinking about that problem,” Ransford said.

The competition was wide open in terms of design rules, Koontz said. The Diggeridoos, a small, brand new team with roots in Hyperloop at Virginia Tech, knew little of tunneling in general, let alone the machine they would build, so they had two initial objectives: learn “everything from the ground up” about tunnel boring machines, Ransford said, and raise the money to build one.

After the team submitted their design and was selected to compete in early 2021, the Diggeridoos built their machine over the summer and in the weeks leading up to the Not-a-Boring Competition in September. A core group of 20 to 30 students with a variety of majors — computer science, mechanical engineering, business — took part in the build or in fundraising for the Underdoge, while industry advisors, many brought in by the team’s faculty advisor, mining and minerals engineering professor Erik Westman, advised them on design.

Finding funding proved to be one of the team’s major sources of uncertainty, said Ransford. “Us being a new team, that’s one challenge because we aren’t established like a bunch of other teams here on campus,” he said. “A lot of people were taking a shot in the dark with us.”

That included 69 donors to the Diggeridoos’ crowdfunding campaign held on the Virginia Tech Jump fundraising platform. The team surpassed a $5,000 campaign goal on the platform.

“Us being a new team, that’s one challenge because we aren’t established like a bunch of other teams here on campus,” Ransford said. “A lot of people were taking a shot in the dark with us.”

Part of the crowdfunding effort was telling their story as a self-described “scrappy” team, said Trace Broyles, the team’s marketing lead.

“We may not be the flashiest or the best, or have metal piping or a million dollars, but we have each other, and the energy and the passion that has carried us to this point,” Broyles said, a week before competing. “We have really been hitting the ground running, trying to improve our outreach and get our entire team out into the world.”

The campaign helped the team raise the $30,000 they needed in total for the Underdoge and its parts. But it added much-welcome morale as well, said business lead Zachary Collins. “It was an emotional boost for us, seeing those parents, other alumni, and people putting in money and putting an effort in for us, because they wanted to see a Virginia Tech team succeed,” Collins said. “Given what we’ve been able to do with such a small budget, anything helps.”

On arrival in Las Vegas, the eight competing teams found their tents and got to assembly. At first, Koontz picked up on the kind of competitive energy he’d seen among design teams before — they kept to themselves. But as they went through the slog of dozens of safety checks per the standards of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, he saw the mood shift.

“As the week went on, everybody kind of figured out that we all had these problems we had to fix over the course of the week,” Koontz said. “We all banded together, and it was a lot more like a multi-team effort. People were borrowing parts. It made it a lot more fun, honestly, meeting all the international teams and talking about how they did this or that, or how their school works, or what it’s like in Germany and the U.K. It became less serious and more: let’s just try to do the best we can. Less of a competition and more of an exposition of the tunnel boring machine.”

The Diggeridoos were inspired by some of the designs they saw. They got to know the Warwick Boring Team from the University of Warwick in the U.K., and observed their technique of extruding concrete behind the machine’s cutter face, extending a set of arms into the soil and pushing off as the concrete set behind the machine. They saw that TUM Boring of the Technical University of Munich also used a pipe-jacking approach, Koontz said, but had created a quick-loading system for pipe segments that worked like the spinning chamber of a revolver.

Pranav Veenam, who designed the Underdoge’s cutter face, remembers the down-to-the-wire energy he felt on the second to the last day in Las Vegas, when teams were allowed to work through the night, long after sunset. “Even if teams understood that they might not be able to actually pass all the safety checks, they were working as hard as they could to try and pass as many of them as they could,” Veenam said. “That was really good to see, that nobody gave up.”

TUM Boring and Swiss Loop Tunneling were ultimately the only two teams to pass all of their safety checks, and TUM Boring alone had the chance to dig a 100-foot tunnel through soil filled with caliche, a layer of soil hardened by carbonates, hard as rock and common in the area. That added to the challenge, Ransford said, and the team ran out of time to dig a complete tunnel.

“Toward the end, we all just wanted to see TUM and Swiss Loop dig,” Koontz said. “We couldn’t, and they had super cool designs. They’re all awesome engineers. We gave Swiss Loop some parts to use so they could try and dig. It was very positive, very inspirational for future designs.”

Other than recognizing an overall winner in TUM Boring, the Boring Company didn’t rank the teams. Instead, it gave out four other goal-oriented awards, including prizes for safety, design innovation, and the top guidance system. Though the Diggeridoos never saw their machine dig, they were able to demonstrate its design for speed, winning the award for fastest launch design.

Ransford said the Diggeridoos accomplished their primary goal in the team’s first year: to have fun. Still, they’ll aim to dig and clinch overall winner in 2022. “Tunneling is hard,” he said. “They told us how hard it is and we understand now from actually trying to do it. By having all of us go to this competition and all of us try hard this year, if we even get a little more successful next year, we’ll push that tunneling future a little further. Which will be really, really cool.”

Competion photos courtesy the Diggeridoo team. On-campus photos by Peter Means.

If you want to have an impact on our students and faculty like those featured in this magazine, go here to support the College of Engineering. For more information, call (540) 231-3628.